A huge find for the OED – a startling antedating for partner meaning ‘spouse’

When the Oxford English Dictionary got involved with Shakespeare’s World, we knew that these documents would provide invaluable data on Early Modern English in everyday, non-print use. What we hoped, but couldn’t be so sure of, was that this project would also produce some changes to the historical record of English so startling and immediately relatable that they can help explain to the general public why it’s worth doing this sort of painstaking work. Early in the project we found an example of the phrase white lie that pushed the record back by nearly two centuries, from 1741 to 1567. But we suspected that better was still to come, and now we’ve found it, with really breath-taking earlier evidence of partner in the sense of ‘spouse’.

When we revised the entry for partner for OED in 2005, we searched hard for earlier evidence of all eleven of its separately defined senses. One sense that couldn’t help but attract a lot of attention was the one that OED defines as (sense 5a):

A person who is linked by marriage to another, a spouse; a member of a couple who live together or are habitual companions; a lover.

Especially in the UK, this use of the word has considerable currency, especially as a convenient means of referring to the ‘significant other’ in a person’s life without any particular implications as to legal marital status, sexuality, etc. As OED notes, it is:

Now increasingly used in legal and contractual contexts to refer to a member of a couple in a long-standing relationship of any kind, so as to give equal recognition to marriage, cohabitation, same-sex relationships, etc.

Where does Shakespeare’s World fit into this picture? Back in 2005, the earliest example of this sense that OED’s researchers could find was from Milton’s Paradise Lost (Book X, line 128):

I stand Before my Judge, either to undergoe My self the total Crime, or to accuse My other self, the partner of my life.

Not only is this example from a core canonical literary author, it is also essentially self-explaining, as part of the longer phrase “the partner of my life”. Other early examples are similar, like this one from Tobias Smollett’s tragedy The Regicide in 1749:

What means the gentle Part’ner of my Heart?

But in 2017, Shakespeare’s World volunteers started to report that they were finding partner meaning ‘spouse’ in correspondence from the late 1500s and early 1600s. I must confess that my initial response was scepticism. I went back and searched text collections such as Early English Books Online again: there were one or two uses in phrases that could (maybe just) be seen as precursors of the use in Milton, but nothing to really suggest that partner had developed the meaning ‘spouse’ by this date. But Shakespeare’s World was definitely turning up the goods, like this example from 1577:

If by death my partner should lose her partner I shall prouide for her out of that litle a competent partners part. as touchinge my partners apparell I haue sent vnto her the graue determynacion of a taylor.

Pulling together the examples showed something else: there were lots of instances, but they were all from the correspondence of two people, Richard Broughton and his wife Anne (née Bagot), writing to members of their close family circle (especially Anne’s father, Richard Bagot). In fact, they began using partner in reference to one another before their wedding. Here is another example, from one of Anne’s letters:

My Euer good brother mr. Higines opinione was, that my Partner mvst bee att the bathe before maye, hie is gone thether & on satter day I shall heare Doctar shurwoodes opinione.

So what is going on here? Perhaps partner was in widespread use meaning ‘spouse’ in the late 1500s and early 1600s, and we just need more access to personal letters, diaries, etc. to give us more examples. But, if so, it’s surprising that we have no other examples from any other source – including other documents that have been transcribed on Shakespeare’s World, as well as other collections of correspondence from the period. Perhaps instead this was something that Richard and Anne Broughton innovated for themselves – it’s not so very surprising a development from the other earlier meanings of partner, and we can say fairly confidently that it was available as part of the potential meaning of the word. And, although Richard Broughton appears a rather unattractive figure from the historical record of his legal and business activities, the picture that emerges from the letters is of two people with a (linguistically) playful side, with anagrammatic respellings such as “Agant Bona” for Anna Bagot, and nicknames for various family members.

For the present, examples of use by both Richard and Anne have been added to the OED entry, with a note:

Early usage history: Quots. 1577 and 1603 come from the correspondence of Richard and Anne Broughton (née Bagot), who use the term repeatedly in referring to one another in correspondence with other members of their family circle. Such use has not been found elsewhere at this date.

But perhaps new evidence can change that picture again. If you find such evidence, please let us know – we’ll be as thrilled as you.

Some great finds for the OED

uncaple – eye-skip, or a new form for the OED?

@parsfan was transcribing a letter from 1715, summing it up as “Basically, a complaint by some Warwick Innkeepers that they haven’t been paid for four months for quartering a troop of Dragoons”. There’s an unusual spelling “uncaple”, which appears at the beginning of the second line here:

Lines from letter in the Collection of Items relating to the Borough and Parish of Warwick, England, Folger MS: X.d.2 (100)

The word clearly means “uncapable”, and at first glance, this perhaps looks like a case of eye-skip, someone skipping ahead to the second “a”, which seems especially plausible as the letter gives the impression of being written in something of a hurry. However, a bit of further sleuthing shows “uncaple” also occurs in a 1629 quotation already in the OED, and there appear to be a number of further examples in the Early English Books Online database of digitized early modern printed books. So, although a lot more research work will be needed, it looks like we may well be onto an addition for the OED here.

An image of the full letter is below, and more information about this manuscript from the Folger catalog may be found here.

the tolfte of November

@mutabilitie spotted this interesting spelling of twelfth as tolfte:

Lines from a letter in the Papers of the Bagot Family of Blithfield, Staffordshire, Folger MS: L.a.586

It comes from a letter from Francis Kynnersley, written in Badger in Shropshire, to Walter Bagot, circa 1620. We’ve not yet found other Early Modern examples of this spelling, but the Linguistic Atlas of Later Medieval English records some similar forms – and, very interestingly, they come from Shropshire, just like this letter. So often you find that when you start to put together isolated bits of information like this, an interesting pattern begins to emerge, and we learn a bit more about the history of English.

Again, an image of the full letter page is below, and information from the catalog record may be accessed here.

by Philip Durkin (@PhilipDurkin), Deputy Chief Editor, Oxford English Dictionary

Shakespeare’s World and updating the OED: a splendid antedating of “white lie”

text from Folger Manuscript L.a.2, a letter in the Bagot Family Papers

“Antedatings” for the Oxford English Dictionary are always exciting, showing that a word or meaning has been around for longer than previously thought. Sometimes, though, they just take your breath away. For instance, the OED’s editors recently prepared a new version of WHITE and its various compounds and derivatives. This involved, among other things, carefully combing through all of OED’s existing quotation files, and numerous online databases of historical linguistic evidence. In this process the earliest example we found of white lie (“A harmless or trivial lie, especially one told in order to avoid hurting another person’s feelings”) was from 1741. Imagine, then, our surprise and delight (and yes, it is delight, rather than lexicographical sour grapes!) when keen-eyed Shakespeare’s World participant mutabilitie found this in a letter from 1567:

Letter from Ralph Adderley I to Sir Nicholas Bagnal, marshal (of army) in Ireland, 1567, Papers of the Bagot Family of Blithfield, Staffordshire (Folger MS L.a.2)

Lines 8/9 give us “Albeit I do assure you he is vnsusspected of / any vntruithe or oder notable cryme (excepte a white lye)”, pushing “white lie” back nearly two centuries earlier than we previously suspected.

An obvious question is why we haven’t added this to the OED the day that @mutabilitie spotted it. In this instance, we’ll need to do a bit more work on this manuscript letter, to be sure of how we want to cite it, and especially date it, in the OED – and we very much hope that the experts at the Folger will be able to cast an eye over that as well.

In other cases, the work involved for the OED will be more extensive, and take longer. The task of revising an OED entry is complex, and typically involves a number of different specialists – for instance, researchers checking numerous data collections for examples of the word (especially ones that are earlier or later, or point to different meanings or constructions); expert definers, assessing how the meaning is described; specialists compiling data on the typical spellings a word has shown through its history; etymologists, tracing how the word has been formed, where it has come from, and how it has been influenced by other languages; bibliographers, scrutinizing how examples are cited and dated and ensuring that the cited text is accurate – and this is before we take account of areas that typically impinge less on the Shakespeare’s World data, such as pronunciations, or definitions of scientific vocabulary. Coordinating all of this work involves an intricate sequence of inter-connected tasks, and inevitably takes time – particularly when your wordlist runs to over a quarter of a million words. That’s why some of the Shakespeare’s World material that will ultimately have a big impact on OED entries will get an enthusiastic “thank you” from OED editors but may not show up in the published dictionary text until it can be incorporated as part of a full revision of the dictionary entry where it belongs. This is probably going to prove the case with the discoveries about taffety tarts and farts of Portugal in two earlier posts: the entries for both taffeta and fart are due for full revision for the OED at some point in the not too far distant future, which will enable us to take full account of how this new information helps transform our understanding of the history of these words.

by Philip Durkin (@PhilipDurkin), Deputy Chief Editor, Oxford English Dictionary

Access to the OED for Shakespeare’s World participants: an important update!

A number of postings on Talk have highlighted exciting finds for the Oxford English Dictionary coming out of the work of Shakespeare’s World participants. Look for blog posts here in the coming weeks on some of these discoveries and how they are informing the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

We are thrilled to have this information for the OED, and intend to make full use of it in revising the dictionary (for more information about the OED and its revision programme see the earlier posting on taffety tarts).

However, we’ve been only too aware that not all participants have access to the online OED (although many people already do, typically through libraries or academic institutions).

We are therefore delighted to announce that, as of now, OUP will be happy to give free access to the OED for any Shakespeare’s World participants who have made more than 500 transcriptions (of up to a line each) in the past year. If you fall in that category and would like access to the OED to help you transcribe and explore these fascinating documents, then please contact us with the subject line ‘Shakespeare’s World OED access’.

by Philip Durkin (@PhilipDurkin), Deputy Chief Editor, Oxford English Dictionary

Some more finds for the OED: portugall farts, fussie smalligs (again), and receitpts

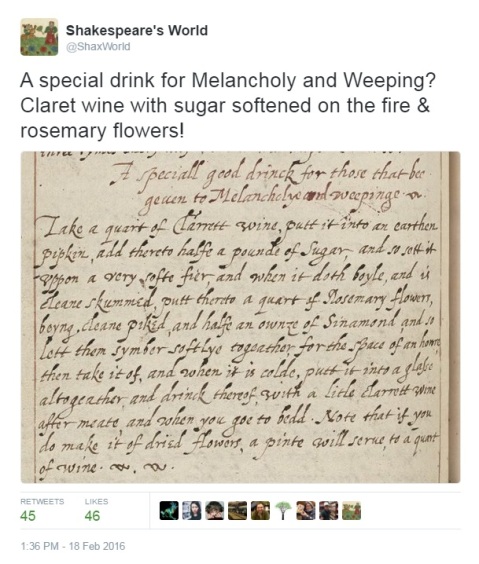

This recipe “To make mackroones or portugall farts”, not surprisingly, raised some eyebrows after it was spotted by @kodemonkey:

The mackroones are macaroons, and the spelling mackroon is already recorded by the OED for the 1600s and 1700s. The portugall farts appear to be the same thing as the “farts of Portugal” which the OED records for the sixteenth century as a specific culinary use of fart (in its usual, embarrassing meaning):

The parallel that French pet (also literally ‘fart’) is similarly used to denote a doughnut or similar air-filled treat suggests strongly that we are indeed looking at a humorous use of the familiar word, giving an insight into the different ideas of decorum – and indeed of what might or might not put someone off eating a pastry – of another age. In fact French dictionaries record (in medieval French spelling) pets d’Espaigne, literally ‘Spanish farts’, dating back as far as 1393. The keen eyes of the Zooniverse community have given us an important pointer for expanding the coverage of this item for OED and a stimulus to include this word soon in OED’s rolling revision programme. (The current version of fart in the dictionary dates back in essentials to 1895 – revising the OED is a Sisyphean task!)

It’s also worth highlighting a few of the less immediately arresting things coming out of Shakespeare’s World that nonetheless get lexicographers and linguists excited. @LWSmith’s blog post On Close Reading and Teamwork drew attention to fussy smalligs probably meaning ‘fuzzy smallage’, as originally spotted by @parsfan. As Laura points out, the spelling fussy for fuzzy isn’t yet in the OED. But looking again at Gervase Markham, OED’s current earliest source for fuzzy (spelt fuzzie) in the very early 1600s, shows that he also wrote about a soft fussie and vnwholsome mosse and about clay of a fussie temper (in contrast to stiffe blacke clay), all of which suggests that another close look at the early history of fuzzy is thoroughly merited. Again, Zooniverse researchers and volunteers have pointed the way for what will be important revision work for the OED.

Finally, @jules spotted the spelling receitpte in a recipe heading:

The word receipt was originally spelt with no p, spellings such as receit being common in early use. It comes ultimately from Latin recepta, but was borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Middle French, in which it had forms such as recette or (in Anglo-Norman) receite. From an early date spellings with a (silent) ‘etymological’ p are found in Anglo-Norman and Middle French and also in English, reflecting awareness of the word’s Latin origin. The hitherto unrecorded spelling receitpte spotted by @jules, with an additional t in front of the p, is really illuminating. This writer clearly knows that the word is written with a silent p. Perhaps receitpte is the result of getting so far in writing the word, remembering about the silent p, and leaving the first t as an uncorrected error. Or perhaps (I suspect more likely) this is a belt-and-braces way of signalling loudly and clearly “you spell this word with a p but pronounce it as though it just had a t”. It would be great to know whether any other –tpt– spellings are lurking in these manuscripts. Transcriptions on Shakespeare’s World, and especially lively discussions on Talk, are just the way we’re going to find that out.

Remember, remember?

By Victoria Van Hyning @vvh

On Halloween day, over a hundred members of the University of Oxford gathered outside the doors of the History Faculty to see a ‘reenactment’ of Martin Luther pinning his 95 theses to the doors of All Saints’ Church. A PhD candidate played Luther, complete with academic robe and a tonsure headpiece probably bought at a party shop. Someone else played Johann Tetzel, hawking indulgences and claiming they had the power to expiate all of our sins. Tetzel personified many of the ills against which Luther was reacting, for instance, the idea that time in purgatory could be minimized through the purchase of indulgences, rendering contrition and repentance unnecessary. Each actor exclaimed to the gathered crowd, garnering applause and knowing titters even though those of us at the back of the pack couldn’t hear much. Nonetheless, when Luther gingerly glued his theses to the door, we all cheered, perhaps a little ironically.

Here we were re-enacting a moment in history that probably never happened. Luther probably didn’t nail his theses to a door so much as send them to various opponents and powerful people in Wittenburg. Yet that imaginary act—that imaginary door—opened a much larger metaphorical door onto religious fragmentation and change in the sixteenth century that very much reverberates across the world today.

For me, as someone who studies some of the consequences of the Reformation that followed Luther’s circulation of his 95 theses, it was important to take an hour out of my research and writing schedule to witness this reenactment. I was curious to see how modern scholars and students, many of whom study the Reformation and its aftermath, would react to this event. Would it be celebratory, didactic, reflective? It was the first two, certainly. People eagerly snapped up the large format prints of the 95 theses that had been made by a local teacher of printing techniques, who had also set out his stall where people could print their own indulgences.

A freshly printed indulgence, and silver in hand.

A freshly printed indulgence, and silver in hand.

As the theses ran out, and the print-your-own-indulgence queue thickened, I drifted away empty-handed, thinking about the difficulties faced by people on all sides of the religious debate in the centuries that followed. When I got back to my office I turned to our Shakespeare’s World data, created by members of this online community, looking for historical evidence of these struggles. Among the many thousands of pages that have been ‘retired’ by the aggregation system, after 3 or more people have transcribed each line, I found a transcription of a letter containing the plea of Sir Francis Norris, the Earl of Berkshire (1579–1622), on behalf of his fellow Catholics. He writes to James I:

How manie noblemen and worthie gentlemen most zealous in the Catholique Religion haue endured, some losse of lands & Livings, some Exile, others impri= sonment, some the effusion of blood and life for the advanncement of y<ex>ou</ex><sl>r</sl> blessed mothers right unto the Scepter of Albion, Nay whose finger did euer ake but Catholiques for y<ex>ou</ex><sl>r</sl> Ma<ex>ies</ex><sl>tie</sl>s present title & dominions? How many fledde to y<ex>ou</ex><sl>r</sl> Court offring them= =selfes as Hostastes for theire freinds, to liue and die in y<ex>ou</ex><sl>r</sl> gratious quar= =rell

V.b.234 367–8 (Unedited transcription from aggregated Shakespeare’s World data, combining the transcriptions of multiple volunteers)

Norris’s current Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) entry does not stipulate that he was a Catholic, and I’ll be contacting the editors soon to suggest an amendment to his entry be made on the basis of this letter. Like amendments to the OED made using Shakespeare’s World data, these changes will hopefully be incorporated and point to the letter when it is hosted on EMMO.

Norris was not alone in his suffering. Countless Catholics, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Quakers, Methodists, Anabaptists, Fifth Monarchists, and many others faced persecution under monarchs and politicians of varying religious persuasions at various times. Monarchs themselves were not free to adhere to their faith of choice without criticism or even the risk of losing power. James II was notoriously suspect for his affinities with Catholics and rumours swirled around him regarding his allegiances, both religious and political.

The Luther reenactment in Oxford fell close to 5 November, Guy Fawkes Day in the UK, also known as Bonfire Night, which (in much of the UK and parts of Canada) ostensibly commemorates the foiling of a poorly-thought-out plot by radical Catholics to blow up Parliament in 1605. I say ‘ostensibly’ because many people are not familiar with the historical precedent for the bonfire (or rather, the recent historical precedent—Bonfire Night is in fact a Catholic appropriation of pre-Christian traditions long established in the British Isles).

Some communities in England burn effigies of the Pope, Guy Fawkes, and other ‘public enemies’ atop their bonfires. Kent in Surrey burnt Donald Trump in effigy in 2016.

The bonfire hosted by the Round Table charitable organization in Oxford does not burn an effigy. Instead, most years the ~30 foot pyre is topped with an empty chair, which opens multiple possible readings. Perhaps it is an invitation to mentally insert your own effigy or maybe the empty chair speaks to our remove from the events of 1605: maybe there is no need to ‘remember, remember the 5th of November’ as the old rhyme goes.

- A grainy shot of the Oxford Round Table bonfire, pre-fireworks and lighting.

I was amazed to find, back in 2007, when I temped as a secretary at a private Catholic school, that parents and children came in on the morning of the 5th asking where they could stash the Guys that their children had made, which would be burned on a bonfire on the school grounds. These Guys were just guys to the children—part of a fun annual ritual—not a Catholic who had tried to blow up Parliament.

The Luther re-enactment and Bonfire Night continue to stir my thoughts about the ways in which cultures mis-remember, and also forget. What are your experiences of cultural re/membering and forgetting?

Transcription aggregation update

Many of our regular contributors will have seen (and indeed been interviewed for!) this article by Roberta Kwok for the New Yorker back in January of 2017. Roberta briefly describes the algorithm that merges the multiple transcriptions of pages by independent volunteers in Shakespeare’s World into a single transcription for a given page. The algorithm is called MAAFT, and is typically used to align genetic sequences. The idea behind this approach to transcription is that it allows us to combine transcriptions of smaller strings with longer strings in the same line. So, if I transcribe only one word on a line, and @parsfan and @mutabilitie transcribe the whole line, my small piece will still be counted by being compared with theirs and then slotted into the right place in the transcription. Zooniverse’s former data scientist and I decided to implement this method in an effort to enable people to contribute even small transcriptions to this relatively difficult project.

The other reasons we went for the MAAFT approach is that it means that anyone to take part in the project who wants to, without having prior paleography training. It’s ok if you make mistakes, because multiple people are transcribing the same material, so if you’ve transcribed a few letters correctly and some incorrectly, the correct ones will get taken through to the final transcription. This method of combining multiple volunteers’ efforts stems from the same scientific practices that underpin Galaxy Zoo, Penguin Watch, and all other Zooniverse projects, and is vital to the acceptance of crowdsourced data by experts in the sciences, humanities and museum and library fields. Enabling independent crowdsourcing, and then putting the results together is supposed to create a rigorous dataset, and I’m sure that it will for Shakespeare’s World in the near future, but we’re in a holding pattern until September, when a new data scientist will start working to unpick and rebuild our text aggregation process.

Rest assured that we’re not losing anyone’s work—it’s all saved in a database—but we’re not currently able to piece the separate transcriptions together reliably. This is why, in part, we have not yet published much data in the Early Modern Manuscripts Online (EMMO) database at the Folger. However, as Philip announced in previous posts on this blog, quite a few interesting finds are already being incorporated into the Oxford English Dictionary, and he says that Talk is the most effective platform for getting crowdsourced updates into the dictionary. Meanwhile our guest scholars from the Early Modern Recipes Online Collective (EMROC) have also been gathering invaluable data for their work via Talk, and many of you have been helping me gather #catholic and #womanwriter sources.

So, for now, one of the best ways to contribute to Shakespeare’s World is to hop on Talk and use those hashtags, for example #paper, #oed, #Catholic and #womanwriter. We hope to have our aggregation sorted soon, and the transcriptions freely available to all.

-By Victoria Van Hyning, @vvh

Four Seasons in Shakespeare’s World…

By Sarah Powell

Cross-posted on The Recipes Project with some slight differences.

One year ago the Early Modern Manuscripts Online project at the Folger Shakespeare Library partnered with Zooniverse to officially launch Shakespeare’s World, in association with the Oxford English Dictionary. What better way to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 2016, than to invite people into our manuscript collection so that we could learn together about the everyday experiences and scribblings of his contemporaries? For 12 months we have been puzzling through thousands of pages from recipe books and correspondence (in 2017, further images and genres will be added).

Screen shot taken from Shakespeare’s World main site

On our first day we put out a world-wide welcome all call to join us in transcribing “handwritten documents by Shakespeare’s contemporaries and help us understand his life and times. Along the way you’ll find words that have yet to be recorded in the authoritative Oxford English Dictionary.”

We were thrilled by the response! Transcribers in Australia, Germany, The Netherlands, UK and USA, as well as elsewhere, promptly jumped on board. At one point, within hours of launching, 300 users were simultaneously transcribing. From that day forward the Shakespeare’s World community was formed.

The handwritten words in Shakespeare’s World manuscripts are far more intimate than what you might read on a printed page. Their immediacy – a letter or recipe written in haste, a letter accompanied by a couple of old ling, a cheese or fresh nectarines, a pewter box of mithridatum and angelica roots sent in the time of plague – is compelling. We hope transcribing on Shakespeare’s World transports our volunteers from the modern day and drops them directly into the midst of the early modern world, with all the noise and smells (good or bad) that this entailed. Through the recipes and letters we encounter busy lives communicating, cooking, negotiating, quarrelling, cajoling, healing, burning, itching, vomiting, scolding, bleeding and more.

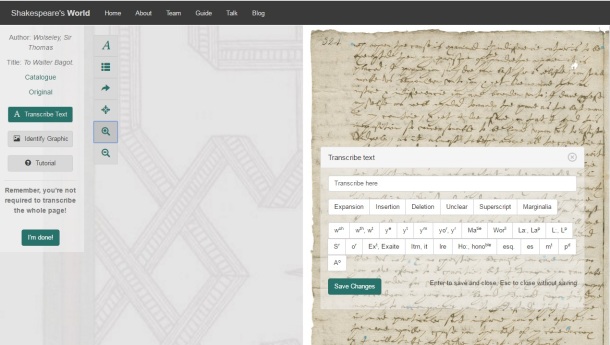

The website itself follows an inductive learning sequence. It has a brief tutorial with sample alphabets to help users identify early modern letters. Users have the option to skip an image if the writing or subject matter is not to their taste. Shortcut buttons make it easy to expand abbreviations (wch / which; wth / with; yr / your).

Here is a snapshot of what you would have encountered, should you have decided to transcribe a letter at 4.05pm EST, December 8, 2016!

Screen shot taken from Shakespeare’s World, 4.05pm eastern time, December 8th 2016

Here is whistle stop tour of our very full year, season by season!

Winter

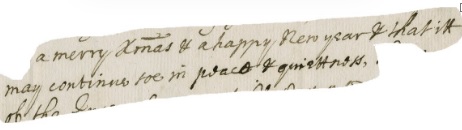

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 14 verso

Shakespeare’s World has a ‘Talk’ platform which hosts interaction between transcribers and the research team, supporting wide-ranging discussions about paleography and specific manuscripts on a daily basis. When users log their transcriptions, they can comment on the image by adding #hashtags. Winter is a time of baking and nesting so it came as no surprise to see that our first #recipes2try were comfort foods such as marmalade, damson plum tart and caraway buns.

Throughout the year Shakespeare’s World transcribers have kept their eyes peeled for potential new early modern words or meanings to add to the OED. They ping these to #PhilipDurkin on Talk using #OED. Winter was probably our busiest time for #OED finds, with a flurry of words highlighted. You can read all about the first forays into word questing on Philip’s February blog post here including the Talk musings over what exactly are “Portugall farts“? (answer: a kind of macaroon).

Spring

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 6 verso

Spring saw a turn to matters of husbandry with animal care figuring largely. Transcribers discussed and observed many tips on keeping one’s horses, sheep, hens and hogs healthy. How to color paper and how to lure an earwig out of your ear with a slice of warm apple, were other charming finds.

Summer

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 10 verso

As well as #OED, another popular tag among our transcribers is #paper. Shakespeare’s World transcribers have been tagging paper and its use as a tool (such as to apply a salve to a wound, or in baking) after learning that Elaine Leong was researching the use of paper in medical and culinary recipes.

One of the liveliest discussions on Talk took place in summer, over a recipe in Margaret Baker’s receipt book for convulsion fits in children, which required a mountain elf’s foot. To read more on paper and the mystery ingredient ‘elf’s foot’, or anything else, please check out our Shakespeare’s World blogs by some great guest authors!

Also catching volunteers’ eyes were birch twigs used as whisks, pomegranate pill (the rind) used to make ink, and powders for childbirth. Timely for summer was a sunburn remedy from the diaries of John Ward, vicar of Stratford-upon-Avon from 1662 to 1681. He recommends a concoction of honey, nettle seed and daffodil roots.

Fall/Autumn

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 11 verso

Moving into September, we were delighted that our number of registered users continued to grow. As the days grew shorter and the leaves changed color, the Shakespeare’s World community rounded up our favorite booze recipes, and the Folger received some excellent volunteer amendments to our catalogue records.

So far over 2,500 people have registered to take part in Shakespeare’s World (we have many more unregistered contributors as well). Together, we have transcribed 91,000 lines on over 3,000 pages. Shakespeare’s World’s #OED work also continues apace. The findings of our volunteers are particularly valuable because although OED lexicographers have considerable access to early modern printed material, they don’t have the same access to manuscript sources. We look forward to these word findings being incorporated into the OED in due course.

Please join us at shakespearesworld.org, if you haven’t already done so! Not only will you love the conversations on Talk, but you will also be helping to transform thousands of digital images of early modern manuscripts into a readable and searchable corpus on EMMO.folger.edu (coming soon in beta). We can tell you from experience that transcribing on Shakespeare’s World is strangely and satisfyingly addictive, like peeking into someone’s mail and Moleskins from four centuries ago. Surprises and discoveries are to be found on every page!

A huge thank you to all of our resident ‘experts’ & to you our community of valued volunteers, citizen humanists, transcribers, volunpeers…whichever term you prefer. Some familiar names on Talk are the brilliant moderators @mutabilitie & @jules – & of course our fantastic volunpeers @parsan, @Greensleeves, @IntelVoid, @Christoferos, @kodemonkey, @Cuboctahedron, @cdorsett, @Tudorcook, @Traceydix, @kerebeth, @Dizzy78, @mmmvv1, @fromere @ebaldwin @Blaudud -but this list is nowhere near comprehensive.

Whether you chime in on Talk, or transcribe anonymously, we couldn’t do it without you. All of us at the Shakespeare’s World team look forward to greeting you back here next year!

Folger MS F.c.21, fol 1r

Follow us on twitter @ShaxWorld

The Mystery of the Elf Hoof

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

It’s not every day that you come across a recipe that calls for elf hoof. Not even when you regularly work with old manuscript recipe books. Nope. Not even when looking at an eighteenth-century grimoire, in which the most unusual ingredient is the white coating (thrush? milk?) scraped from a newborn’s tongue.

When I spotted @MyraMo and @mutabilitie discussing Margaret Baker’s remedy ‘For Convolchen fetts in yong Children’, I was initially drawn in by @MyraMo’s question about mouse heads and afterbirths. (Who wouldn’t be?) But the recipe became even more intriguing when @mutabilitie commented:

I reckon the ten-clawed hoof of a mountain elf mentioned at the beginning would have prevented anyone from actually trying out this recipe – probably just as well!

Afterbirth? Uncommon, but not unexpected. After all, I’d come across dried mummy, menstrual blood, spit, feces, and urine before. Mouse head? That, as it turns out, was merely a misreading of ‘dead man’s head’. While shocking to modern sensibilities, skull was an ingredient common enough to be listed in official pharmacopoeia. Elf hoof!? That was entirely unexpected—and certainly not a misreading:

Take the houf of an Elfe it is best that lives in the mountaine & hath tenn clawes upon one foote one of those clawes must be rasped and made into very fine pouder.

I didn’t initially dismiss the possibility of Margaret Baker truly meaning elf hoof. I’ve previously looked at the classification of hobgoblins and their ilk, but had not encountered any descriptions of the medicinal uses of supernatural creatures’ body parts. Elves, like any other supernatural being, could help or hinder humans. Given that early modern medicine regularly included human body parts, which were seen as particularly efficacious, surely supernatural body parts would be even better.

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

That said, ‘elf hoof’ was more likely to refer to some herb. The OED didn’t turn up anything obvious except for elf dock and elfwort, alternative names for elecampane. Culpeper’s The English Physician (1652) notes that this herb grows in shady places and, governed by the sun, is hot and dry in the third degree. It even looks like the sun and its root is like a hoof with claws. One species, orestion, grows specifically in the mountains, according to Robert Hooper (1817). As a stimulant and tonic, it is useful in treating old coughs, shortness of breath, windy stomachs, stopped menses and urine, gout, sciatica, and stitches in the side caused by the spleen. ‘Elf-shot’, a term dating back to the Anglo-Saxons, was still in early modern use to describe certain physical and mental disorders. For example, sharp and shooting pains, such as stitches, gout or sciatica, might be elf-shot.

Pretty convincing. The mandrake, however, is another contender. In The Compleat Herbal of Physical Plants (1707), John Pechey noted that it grows in woods and shady places and is a good narcotic. Culpeper, in the Pharmacopia Londinensis (1718), advised against the use of mandrake roots because of the dangers posed by it being cold in the fourth degree. It could, however, be useful for ‘such as have a frenzy’ (269). The mandrake, thought to be luminous, was governed by the moon and, as such, could be used to treat ailments such as epilepsy, an ailment associated with the full moon. Folklorists Thomas Dyer and Richard Folklard describe the mandrake’s various magical uses, ranging from love charms to treasure finders. Resembling the human form, mandrake roots were sometimes sold as little mannikins and (in early modern France) they were sometimes seen as a species of elf. Those who possessed mandrakes often cared rather elaborately for it, providing it with food and drink, much in the same way that one might try to keep other supernatural creatures within the household happy.

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

But which fits better with the remedy as a whole? In addition to elf hoof, skull and afterbirth, the ingredients were leaf gold, peony, cowslip, mithridate, nutmeg and amber. The remedy suggests that the convulsions were epileptic; it was to be administered at the change of the moon and several of the ingredients were intended to counteract the effects of the moon. For example, gold, amber and peony were all ruled by the sun. Other ingredients were intended as protective, such as the mithridate (a cure-all), the man’s skull (like cures like, in that epilepsy was also a disease of the head), and the afterbirth (acting symbolically). The ingredients in general had sedative and anti-spasmodic properties.

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

Elecampane fits the description of elf hoof in that there is a specific type grows in the mountains, it treats ‘elf-shot’ (of which epilepsy might be one type), and it is associated with the sun like most of the other ingredients. Mandrake, in contrast, stands out as being a cold ingredient. It fits in other ways, however: it had narcotic properties and was associated both with diseases of the moon and elves.

The recipe blurs the magical and medical in intriguing ways with several of its ingredients and timing of administration. It also suggests the complicated pathways of transmission over time. Elf hoof may very well have been a local term, or one that simply made it into Margaret Baker’s collection when she heard it from someone else and it took her fancy. The remedy also hints at the continued existence of much older ideas: sun and moon, elf-shot, and mannikins. In the end, for the modern reader, Margaret Baker’s description is both incredibly specific and frustratingly vague. The elf hoof that she describes in great detail no longer corresponds to our modern terms, leaving a recipe that seems more mysterious than it probably was at the time.

What do you think it was: elecampane, mandrake… or elf?

Living in Shakespeare’s World

|

Recent Comments