By Elisabeth Chaghafi (@mutabilitie on Talk)

The Newsy Baronet: how Richard Newdigate (per)used his newsletters

Cross- posted on The Collation

Large collections of books or manuscripts may be interesting for two reasons: the actual content of the items they contain, and also what they reveal about the collector who compiled them. The Folger’s Newdigate family collection of newsletters (Folger MS L.c.1-3950) is an excellent example of this. The inclusion of these newsletters in the Shakespeare’s World site has led to the transcription of a large portion of them, which in turn leads to a greater understanding of the collection as a whole. This collection is fascinating partly because of its sheer scale—well over 3,000 newsletters, most of them collected by Sir Richard Newdigate, 2nd baronet (1644-1710)—making it a fairly comprehensive archive of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century news. But the collection also contains quite a few clues about Newdigate himself and the ways in which he read and used his newsletters. Some of these traces of Newdigate’s news-reading habits (especially his underscorings) are easily overlooked. When the newsletters are studied in bulk, however, patterns emerge that allow modern readers to witness Newdigate’s strategies of gathering, comparing, and evaluating news from several manuscript and print sources.

To begin by stating the obvious: the second baronet Newdigate was clearly a particularly avid reader of news—something of a news junkie, in fact. He subscribed to different newsletters that covered both domestic and international news, including the popular Dyer newsletters. Dyer was the most successful commercial provider of scribal news and had subscribers who lived as far away as Ireland.1 There appear to be no Dyer newsletters in the collection dated after the second baronet’s death, however, which may be an indication that his son (also called Richard Newdigate) did not entirely share his father’s news-obsession and allowed the subscription to lapse. In addition to the newsletters that now make up the collection, Newdigate subscribed to printed gazettes (several newsletters have traces of offsetting that show the gazettes were often sent in the same packet, although only one of them, L.c.2360 (2), survives as part of the collection).

That Newdigate subscribed to multiple newsletters and gazettes might not be so very special, because the late 17th century was a news-hungry period, but Newdigate’s own annotations indicate that he not only used his newsletters and gazettes for his daily news fix but also carefully filed them away for future reference and sought to fill gaps in his collection in a quest for “completeness.” On L.c.420, for example, Newdigate wrote a note (later crossed out) that indicates the newsletter may at some point have been placed at the top of a box or bundle of newsletters: “News from Ian: 76/7 to Ian 77/8 but many wanting at first.” There are similar notes on several other letters, most of them in Newdigate’s handwriting.

L.c.79 contains a list of “Gazetts wanting”—though all number are crossed out, so Newdigate may eventually have managed to get hold of them after all. In a few cases, Newdigate left a note on newsletters that had arrived without the gazette (which apparently cost an extra twopence), as on L.c.2352, which has a note that reads: “2d overchardg no Gazet in it.” He also endorsed some newsletters with their dates (and in some cases the type of newsletter, such as D. N for “Dyer Newsletter” in the endorsement of L.c.3155) and instructed a servant, who signed his initials “I. S.” or “I.Sc.”, to go over old bundles and double-check them for newsletters that were out of sequence or missing—two of his notes survive on L.c.1513 and L.c.14 (b).2

While Newdigate’s system for archiving his newsletters suggests they were important to him and he was keen to collect and preserve them, this did not necessarily make him any more scrupulous about keeping them in a pristine state than the average person. This collection contains the usual account notes, calculations, and drafts of leases and legal agreements that the recipients of early modern letters routinely used address leaves for—some of them in Newdigate’s own hand, while others are in the hand of a person who also docqueted newsletters in preparation for filing (perhaps his secretary). On one of the earlier newsletters, sent in 1674, (L.c.107), Newdigate went even further and covered the entire address leaf in a draft for a letter to an unnamed person, instructing him to do something about the appalling state of disrepair that several highways had fallen into, “so that no Coach nor horse man or woman could passe without much Danger and Difficulty.”3

To one of the later newsletters (L.c.3156) he added the cryptic note “This they tore in the Nursery”—which makes slightly more sense if you bear in mind that the person who franked most of Newdigate’s non-Dyer newsletters from London (i.e. who exercised his privilege to send letters without postage, and thus saved Newdigate money), was an MP called William Stephens, who also happened to be his son-in-law. Thus, presumably the newsletter meant for Newdigate had accidentally been shredded by his own darling grandchildren, so he was forced to obtain another copy elsewhere!4 But Newdigate also occasionally used available space on newsletters to copy some poetry (Francis Quarles’ “My Sins are Like the haires upon my head” on the address leaf of L.c.192 and an elegy for the Earl of Rochester, who had died six months earlier, on L.c.1170), to make an—unsuccessful—attempt at turning his own name into an anagram, stumbling after “Grace and” (L.c.185) and memoranda to himself and others that had no obvious connection to the newsletters they were written on, such as a note to “Enquire for Mr Palmer Glover Leather seller at Mr Pelcoms a Milliner at the Golden Goat in Cheap side” (L.c.1329), or another one that shows Newdigate in pursuit of yet more sources of news in February 1695/6: “Mem let Iohn Merry enquire at Nuneaton ffor the News cald the Post boy & Flying post & borrow them at night. Sparrow may bring them up” (L.c.2589).

While we don’t know exactly who John Merry was, we do know that he was not the only person to keep Newdigate supplied with news. The newsletters contain references to a whole network of people whom Newdigate at some point employed to forward him newsletters, or sometimes copy them for him. For example, one newsletter in the collection (L.c.816) was originally addressed to a certain Ralph Hope in Warwick and subsequently redirected to Newdigate. This was not a one-off, however. The collection also contains a letter from Ralph Hope to a Mr Johnson (L.c.520) in which he outlines the reasons for a current dearth of news and refers to a gazette enclosed with the letter, suggesting Hope routinely acted as a news-agent. Additionally, the letter provides a clue that the note to Newdigate at the end of L.c.422, which is in the same handwriting, was also written by Ralph Hope—as were a number of the earlier newsletters in the collection, including, but not limited to L.c.230, which Newdigate endorsed “R. H Newes being a transcript of Sir Joseph Wiliamson.” Nevertheless, Newdigate was not always entirely happy with the service provided by Ralph Hope. One newsletter (L.c.114) contains several corrections in Newdigate’s hand (changing “Lord Vaughan” to “Arlington,” inserting words that the newswriter had apparently omitted and correcting “gagering” to “gathering”), followed by a reproachful note that reads: “Mr Hope Pray peruse this, & make sence of it if you can without the amendments above, & hereafter pray seal all the letters which you send to Your freind R N.” Ouch.

Richard Newdigate did not confine himself to adding snarky notes, memoranda, and bits of poetry to his newsletters, however. As his note to Ralph Hope indicates, Newdigate promptly amended errors. Thus he also corrected the date of L.c.10 (another one of Hope’s) from “ffeb the 2d” to “Ian: 31”; changed “yeild” to “yeilded” on L.c.2295; “the byeing” to “them by raising” on L.c.2386; “Buckingham shire” to “Bedford” on L.c.2584; and the misspelt place names “Torkey” and “Best” to “Turkey” and “Brest” respectively on L.c.2590.

Other notes reveal that Richard Newdigate was a critical reader of news as well as a pedantic one. In one case he questioned the newswriter’s ambiguous use of “here” in a news item, adding “qu. Where? at Vienna he meanes at London I suppose” (L.c.2352). At other times he responded skeptically to implausible stories, adding “qu very unlikely” to an unsupported report that a man was in the process of raising and clothing an entire regiment, all at his own expense (L.c.2575); sometimes he noted his intention to seek out more details about a story, as with a report involving a corrupt colonel in L.c.2427 (“Mem write Sir I K to know who is Corub Grubs Colonel & What becomes of this Affair”), or to find confirmation from an authoritative source. Next to a news item about the murder of a tax collector by an angry mob after a number of poor people had had their goods unlawfully seized because they were unable to pay their taxes (L.c.2585), Newdigate added the guarded comment: “This is very remarkeable, but I stay for a confirmation in the Gazet.” On a different occasion, however, when he was certain the newsletter was incorrect regarding Sir Nathan Wright’s appointment as knight of the shire for Warwickshire (L.c.2944) he did not hesitate to note his discontent and complain to the people responsible: “this a [sic] very great Untruth & so I have written the News writer Word RN.”

Bottom: Folger MS L.c.2585, 1v detail

The letters also contain a large number of underlined passages and reader’s annotations in Newdigate’s handwriting that collectively reveal something about his reading habits as well as the kinds of news items that attracted his particular interest. One key interest that probably sounds familiar to a lot of modern news-readers was stories relating to crime: he underlined accounts of various murders and “self-murthers,” as well as robberies, assaults, and duels. For example, on a page from L.c.2375, Newdigate underlined and glossed “A Duell,” “An Assault,” “Duell.” He was also interested in news about lotteries and naval news, especially stories involving the capture or destruction of French ships, which he repeatedly glossed with notes such as “French losse” (e.g. on L.c.2289), “French prizes taken” or “French Misery” (L.c.2404), and he was keen to note instances of “French Treachery” (L.c.2377 and L.c.2589) or “Iacobite insolence” (L.c.2203 and L.c.2386).

A few of the newsletters not only contain underscoring and brief annotations by Newdigate, but also a summary note on the address leaf that compiled all of the news items he had highlighted in one place. Examples of such notes can be found on L.c.2110 and L.c.2152, the latter of which begins with the exciting news that the Earl of Portland may have found a way of stopping his hiccup by “laying the entralls of Lamb to his stomach” (warm entrails, as Newdigate later amended, perhaps thinking that detail might turn out to be important).

These summary notes suggest that Newdigate’s annotations and underlinings in the newsletters were not simply something he did habitually as part of the reading process, but that he actually wanted to preserve the most interesting pieces of information he had gleaned from the newsletters, so he would be able to refer to them again later. This can also be seen in L.c.2285, one of the most copiously underscored and annotated newsletters in the collection, dated 10 February 1693/4. The first page alone has four annotations by Newdigate (or five, depending on whether you consider “Englds Danger” part of the annotation on “French Insolence in H of Com” or not). What is striking about them is the peculiar way some of them are worded: “Baden Prince ill in Engld,” “Scot Dr dead this week,” and “Collonels New.” In all of these, as well as in “Highway men 3 seized” on the next page, Newdigate’s annotations are written in a format that brings the most important keywords to the front of the note, as you might in an index. L.c.2286, the next item in the collection is in fact a compilation of all the underlined bits of L.c.2285, with marginal glosses that are identical to Newdigate’s annotations (though “Englands Danger” has been dropped, perhaps because it was considered redundant).

Right: compiled list of note-worthy points (Folger MS L.c.2286, 1r)

While L.c.2286 is the only example of such a news digest in the Folger’s collection, and it is possible that Newdigate eventually abandoned the idea as too troublesome or not as useful as he had originally thought, the way in which Newdigate marked his newsletters after 1694 suggests that he continued to underline interesting passages with a view to later compilation. In L.c.2589, he labelled his annotations with alphabetical letters ranging from a-g, which only makes sense if he intended to write (or instruct someone else to write) an index or digest afterwards. On the second leaf of L.c.2379 (shown below) is a particularly good example of the style of annotation that gradually seems to have become Newdigate’s preferred format: a combination of underlining, numbering, and insertions that, when read in the correct sequence, became a lightly-condensed version of the news item in question. So for example, the second underlined news item on that particular page would have turned into “project by Doctor Chamberlaine to raise 2 Millions of money without burthening of the Subjects,” while in the last highlighted item on the page (continued along the margin), Newdigate’s version omits the gory detail of the two failed suicide attempts, arriving at just “Self Murther by a Stocking fframe knitter in Moore fields.”

Since this system of annotating would have required additional effort on Newdigate’s part, because he had to think about how to rephrase those news items and which words to insert as he was reading, it also only makes sense if either he or one of his servants at least intended to compile them into a news digest similar to L.c.2286 at a later point.

Collectively, Richard Newdigate’s many underlinings, annotations, and memoranda on his newsletters do two things. They provide a glimpse of the ways in which early modern readers in the late 17th and early 18th century obtained and consumed news as a commodity, and they also sketch out the picture of one particularly news-hungry individual: a newsy baronet who compiled and curated his own collection of news over the course of several decades. From his own notes, Newdigate emerges not only as an avid collector, but as a perceptive, critical reader who thought carefully about the news he consumed and preserved a healthy sense of skepticism even towards news he considered “remarkeable,” waiting for them to be confirmed through the gazette or through his private news network.

Elisabeth Chaghafi is based at Tübingen University. Her research mainly involves Edmund Spenser or book history (or both), but she also likes palaeography and moonlights as a researcher and moderator on Shakespeare’s World.

- On the address leaf of L.c.3395, the words “To Sr Richd Kenne” have been struck out, which points towards Sir Richard Kennedy, 4th baronet of Newtownmountkennedy (c. 1686-1710). Evidently Dyer’s list of subscribers was ordered by first name and the newswriter accidentally selected the wrong Sir Richard. For a detailed account of Dyer’s career see Alex Barber’s article “‘It is not easy what to say of our condition, much less to write it’: the continued importance of scribal news in the early 18th century.” Parliamentary History, v. 32, pt. 2 (2013), p. 293-316.

- “I. S.” may have been John Scott, whose name is written on the address leaf of L.c.1657. For other archiving methods see Heather Wolfe’s 2013 Collation post on Filing, seventeenth-century style.

- The letter is written on behalf of “my Master”—probably Newdigate’s father, the first baronet, who was still alive at the time. We can tell that this is the second Richard Newdigate’s handwriting, because it matches that of three signed letters in the Folger’s collection (), which he sent to his brother-in-law Sir Walter Bagot in 1676.

- The handwriting is less clearly identifiable as Newdigate’s than the other samples (although it looks similar to the somewhat shaky writing on L.c.2944), so an alternative explanation would be that the note was written by Stephens, who invoked the image of the newsletter being torn in the nursery by his children as a way of deflecting his father-in-law’s anger about the potential gap in his newsletter collection.

Shakespeare’s World launches Newdigate newsletters!

By Heather Wolfe (@hwolfe on Talk)

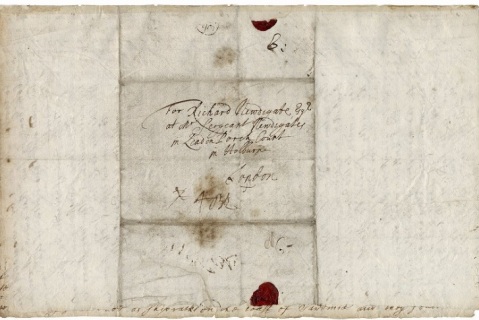

Folger MS L.c.411, Letter to Richard Newdigate, 1676 December 16

Thank you to all those who transcribed the first batch of data on Shakespeare’s World–our thousands of pages of recipes and letters are now being edited and placed on Early Modern Manuscripts Online (EMMO). The remaining recipes and letters will be available until they are completed, but next up we have a whole new dataset: an incredibly fascinating collection of nearly two thousand manuscript newsletters containing court and parliamentary news and foreign affairs from the Continent. These are part of a larger collection of 3,954 newsletters known as the “Newdigate Newsletters” because they were sent to three consecutive generations of the Newdigate family of Arbury Hall, Warwickshire, between 1674 and 1715. More information about this collection can be found in the finding aid. The newsletters were acquired by the Folger from Hodgson & Co. in the July 19, 1956 sale of 17th and 18th century books from the private library of the Newdigate family at Arbury Hall, lot 227.

Despite the fact that printed newspapers were circulating in the late 17th century, handwritten newsletters continued to be an important source for the spread of domestic and international news. Print and manuscript newsletters played different roles in the dissemination of information, and people often acquired both in order to widen their understanding of events and cut through the propaganda. Just like today, different sources might provide different accounts of an event.

Under the auspices of Sir Joseph Williamson (1633-1701), Secretary of State and Keeper of the State Papers, and his Chief Clerk Henry Ball, a small group of scribes produced approximately two hundred newsletters per week which were dispatched on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. Newsletters issued by the Secretary of State’s office were principally delivered to government agents, but were also made available to an exclusive list of subscribers to which the Newdigates belonged. The topics covered in the newsletters are wide ranging, including court gossip, commercial and maritime relations in the English Atlantic and Indian colonies, the Popish Plot, and parliamentary controversy. The newsletters provide rare insight into events of notable historical significance, such as William Penn’s involvement with the early Quaker movement, the indictment of Titus Oates, and early accounts of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Northwest Passage, and Prince Rupert. These are all from the first 2,100 newsletters, which were transcribed by Philip Hines in 1994 and are available by subscription as part of ICAME (the International Computer Archive of Modern and Medieval English). The last 1,850 newsletters, however, have not been read from beginning to end, so your transcriptions will provide historians with a first glance into the entire Newdigate archive, revealing the full contents for the years 1692-1715.

Things to look out for: One hundred and fifty newsletters within the Newdigate family collection are by John Dyer (1653?-1713). Dyer’s newsletters are marked in the Collection with the abbreviation “DNl” (for “Dyer’s Newsletter”). Dyer began writing newsletters as early as 1693 and was frequently brought before the House of Commons on charges of libel and sedition. Nonetheless, Dyer’s newsletters were widely disseminated and became one of the chief sources for English news on the Continent in the early eighteenth century. Several other annotated abbreviations appear throughout the collection, especially in the period 1708-1709: nNL (New newsletter), oNL and News Old (Old newsletter), and WNL (Williamson Newsletter). Offsetting (faded printed residue) on a number of the newsletters provides evidence that the newsletters were usually sent out with a one page printed newsletter, possibly the London Gazette. Also, as you’ll read below, we are interested in identifying deletions and mistakes!

Our first guest researcher for this phase is Dr. Alex Barber of the University of Durham. Alex spent time with the newsletters during a three month fellowship at the Folger, but there was no way he could read all of the untranscribed newsletters in that amount of time or systematically compare them to the many other collections of scribal newsletters in other repositories. Transcription of our newsletters will allow for easier comparison to these other newsletters and provide insight into the extent to which they were “curated” for specific recipients.

Alex produced an important article in the journal Parliamentary History as a result of his fellowship, but that was only the tip of the iceberg in terms of his (and our) fascination with the newsletters, and he returned again in January 2018 to examine them further. In his own words: “Despite the publication of the article there was a serious problem: there was too much material here and it did not suit my purposes at the time. I was writing an intellectual history of the freedom of the press and did not have the time to complete a thorough investigation of the archive. I returned to the Folger and the Newdigate archive in January 2018 with the intention of revisiting some of my ideas, to consider what shape a bigger project on scribal news might take and, most importantly of all, to consider whether I was still interested in the strange world of scribal news. The answer, thankfully, is yes. I am fascinated by the topic in general and by the Newdigate newsletters in particular. Re-reading them I was struck by sets of questions that, as yet, I have no answers to. I can identify easily enough the Dyer letters – but who wrote the other letters; are they official, do they come from the Secretary of State’s Office, or are they another form of commercial news? I love finding quirks in the letters: sections where there are substantive crossings out (can the obscured text be deciphered?) and mistakes. I am obsessed with the skill of the letter writer – the ability of the scribe to fill the page correctly and I am always fascinated by whether the individual scribes can be identified. In other words, whilst I love finding out information from the letters (and considering where the information comes from), I want to think about the archive as a cultural form and eventually work towards a bigger project concerned with the cultural power of news writing.”

Welcome to the team, Alex! In addition to Alex @awbarber, a warm welcome to another new guest researcher Nina Lamal @NINALA. Nina is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Antwerp. Her research focuses on early modern book and communication history. She is currently finishing the first bibliography of Italian newspapers entitled Late with the news. Italian engagement with serial news publications in the seventeenth century 1639–1700, which will be published by Brill. She is particularly interested in how English news sources may have influenced or been influenced by Continental sources. As well as our new guest researchers, the project will continue to be supported by our wonderful moderators @mutabilitie and @Christoferos, Folger paleographer Sarah Powell @S_Powell, Oxford English Dictionary editor @philipdurkin, and ShaxWorld co-investigators Heather Wolfe (Folger curator of manuscripts) @hwolfe and Victoria Van Hyning @vvh. We look forward to this next phase of Shakespeare’s World.

There are many other ways to conceptualise the importance of scribal news, perhaps most obviously how it was produced, distributed and consumed—and as ever ShaxWorld volunteers are encouraged to pursue these and raise questions and lines of research on Talk.

Welcome to the next phase of Shakespeare’s World….

By Heather Wolfe (@hwolfe on Talk)

Folger MS V.a.429: front cover

Welcome to the next phase of Shakespeare’s World! The results of your work with the Folger Shakespeare Library’s recipe books and letters has been truly astounding. Here’s what you accomplished: thousands of new transcriptions, antedatings added to the Oxford English Dictionary, hundreds of corrections made to our finding aids, successful experiments with historical recipes in the kitchen, and more. You have made this grand experiment a wonderful success so far. Who would have thought that so many people would be interested in reading English secretary hand! We are now busily encoding your transcriptions in TEI-P5 (basically, adding pointy brackets with descriptive words inside them to make them machine-readable) for inclusion in Early Modern Manuscripts Online Project.

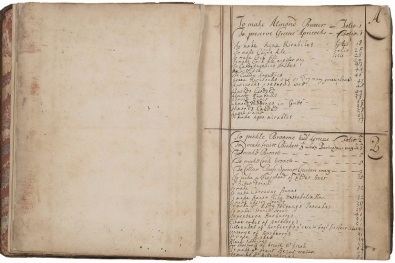

Folger MS V.a.429: folio ii verso || folio iii recto, Index. A-B

The timing for your work on the recipe books could not have been better, because here at the Folger we have started a massive interdisciplinary and collaborative research project funded by the Mellon Foundation called Before Farm To Table: Early Modern Foodways and Cultures. The sort of investigations we want to do during this project would simply not be possible without the transcriptions contributed by our many Shakespeare’s World volunteers. As part of Before Farm to Table, we are hiring a digital postdoctoral fellow who will make the transcriptions available in a variety of innovative ways so that a wide range of audiences can make use of them. In the meantime, through conversations with researchers and useful classifications on the Talk pages, you have provided the basis for a number of conference papers. So a big thank you to all of you!

Four Seasons in Shakespeare’s World…

By Sarah Powell

Cross-posted on The Recipes Project with some slight differences.

One year ago the Early Modern Manuscripts Online project at the Folger Shakespeare Library partnered with Zooniverse to officially launch Shakespeare’s World, in association with the Oxford English Dictionary. What better way to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 2016, than to invite people into our manuscript collection so that we could learn together about the everyday experiences and scribblings of his contemporaries? For 12 months we have been puzzling through thousands of pages from recipe books and correspondence (in 2017, further images and genres will be added).

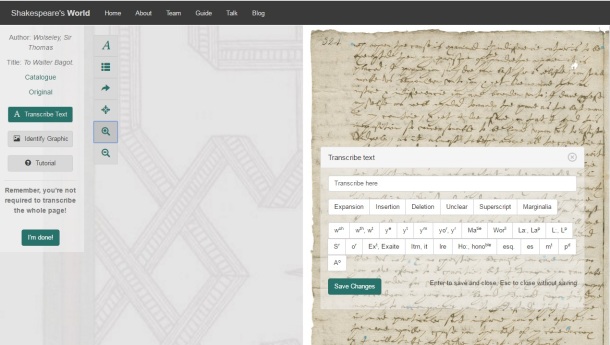

Screen shot taken from Shakespeare’s World main site

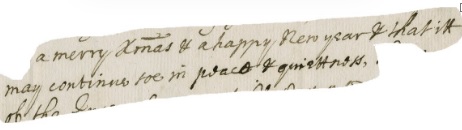

On our first day we put out a world-wide welcome all call to join us in transcribing “handwritten documents by Shakespeare’s contemporaries and help us understand his life and times. Along the way you’ll find words that have yet to be recorded in the authoritative Oxford English Dictionary.”

We were thrilled by the response! Transcribers in Australia, Germany, The Netherlands, UK and USA, as well as elsewhere, promptly jumped on board. At one point, within hours of launching, 300 users were simultaneously transcribing. From that day forward the Shakespeare’s World community was formed.

The handwritten words in Shakespeare’s World manuscripts are far more intimate than what you might read on a printed page. Their immediacy – a letter or recipe written in haste, a letter accompanied by a couple of old ling, a cheese or fresh nectarines, a pewter box of mithridatum and angelica roots sent in the time of plague – is compelling. We hope transcribing on Shakespeare’s World transports our volunteers from the modern day and drops them directly into the midst of the early modern world, with all the noise and smells (good or bad) that this entailed. Through the recipes and letters we encounter busy lives communicating, cooking, negotiating, quarrelling, cajoling, healing, burning, itching, vomiting, scolding, bleeding and more.

The website itself follows an inductive learning sequence. It has a brief tutorial with sample alphabets to help users identify early modern letters. Users have the option to skip an image if the writing or subject matter is not to their taste. Shortcut buttons make it easy to expand abbreviations (wch / which; wth / with; yr / your).

Here is a snapshot of what you would have encountered, should you have decided to transcribe a letter at 4.05pm EST, December 8, 2016!

Screen shot taken from Shakespeare’s World, 4.05pm eastern time, December 8th 2016

Here is whistle stop tour of our very full year, season by season!

Winter

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 14 verso

Shakespeare’s World has a ‘Talk’ platform which hosts interaction between transcribers and the research team, supporting wide-ranging discussions about paleography and specific manuscripts on a daily basis. When users log their transcriptions, they can comment on the image by adding #hashtags. Winter is a time of baking and nesting so it came as no surprise to see that our first #recipes2try were comfort foods such as marmalade, damson plum tart and caraway buns.

Throughout the year Shakespeare’s World transcribers have kept their eyes peeled for potential new early modern words or meanings to add to the OED. They ping these to #PhilipDurkin on Talk using #OED. Winter was probably our busiest time for #OED finds, with a flurry of words highlighted. You can read all about the first forays into word questing on Philip’s February blog post here including the Talk musings over what exactly are “Portugall farts“? (answer: a kind of macaroon).

Spring

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 6 verso

Spring saw a turn to matters of husbandry with animal care figuring largely. Transcribers discussed and observed many tips on keeping one’s horses, sheep, hens and hogs healthy. How to color paper and how to lure an earwig out of your ear with a slice of warm apple, were other charming finds.

Summer

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 10 verso

As well as #OED, another popular tag among our transcribers is #paper. Shakespeare’s World transcribers have been tagging paper and its use as a tool (such as to apply a salve to a wound, or in baking) after learning that Elaine Leong was researching the use of paper in medical and culinary recipes.

One of the liveliest discussions on Talk took place in summer, over a recipe in Margaret Baker’s receipt book for convulsion fits in children, which required a mountain elf’s foot. To read more on paper and the mystery ingredient ‘elf’s foot’, or anything else, please check out our Shakespeare’s World blogs by some great guest authors!

Also catching volunteers’ eyes were birch twigs used as whisks, pomegranate pill (the rind) used to make ink, and powders for childbirth. Timely for summer was a sunburn remedy from the diaries of John Ward, vicar of Stratford-upon-Avon from 1662 to 1681. He recommends a concoction of honey, nettle seed and daffodil roots.

Fall/Autumn

Folger MS V.b.232, folio 11 verso

Moving into September, we were delighted that our number of registered users continued to grow. As the days grew shorter and the leaves changed color, the Shakespeare’s World community rounded up our favorite booze recipes, and the Folger received some excellent volunteer amendments to our catalogue records.

So far over 2,500 people have registered to take part in Shakespeare’s World (we have many more unregistered contributors as well). Together, we have transcribed 91,000 lines on over 3,000 pages. Shakespeare’s World’s #OED work also continues apace. The findings of our volunteers are particularly valuable because although OED lexicographers have considerable access to early modern printed material, they don’t have the same access to manuscript sources. We look forward to these word findings being incorporated into the OED in due course.

Please join us at shakespearesworld.org, if you haven’t already done so! Not only will you love the conversations on Talk, but you will also be helping to transform thousands of digital images of early modern manuscripts into a readable and searchable corpus on EMMO.folger.edu (coming soon in beta). We can tell you from experience that transcribing on Shakespeare’s World is strangely and satisfyingly addictive, like peeking into someone’s mail and Moleskins from four centuries ago. Surprises and discoveries are to be found on every page!

A huge thank you to all of our resident ‘experts’ & to you our community of valued volunteers, citizen humanists, transcribers, volunpeers…whichever term you prefer. Some familiar names on Talk are the brilliant moderators @mutabilitie & @jules – & of course our fantastic volunpeers @parsan, @Greensleeves, @IntelVoid, @Christoferos, @kodemonkey, @Cuboctahedron, @cdorsett, @Tudorcook, @Traceydix, @kerebeth, @Dizzy78, @mmmvv1, @fromere @ebaldwin @Blaudud -but this list is nowhere near comprehensive.

Whether you chime in on Talk, or transcribe anonymously, we couldn’t do it without you. All of us at the Shakespeare’s World team look forward to greeting you back here next year!

Folger MS F.c.21, fol 1r

Follow us on twitter @ShaxWorld

nunc est bibendum…

Citizen-humanist (& one of our fabulous volunteers) @Greensleeves made a delicious sounding cherry brandy earlier this year using a recipe from Shakespeare’s World. It involved steeping cherries in brandy for months, with sugar, cinnamon & cloves. If you fancy trying out some of our ‘drinks’ recipes too, here are a selection taken from the project thus far. The main ingredients are also noted below. Most list water as an ingredient, though it is referred to differently as cold water, fair water, spring water or raw water. Another theme they have in common is time (you will need the patience of 6 or 7 days, 3 weeks…etc!). A huge thank you to all of our citizen-humanists who tagged &/or transcribed these recipes.

Grape Wine

To make Wine of graps:-

Ingredients: clusters of grapes, including the rotten ones!

Ale

Cocke Ale

Ingredients: 1 cockerel, 2 quarts of the best sack, 8 gallons strong ale, 4lb raisins, 1/4lb dates, a large nutmeg, cloves, mace & sugar.

Lemon Wine

Lemmon Wine

Ingredients: 8 lemons, 2lb sugar & spring water.

Gooseberry Wine

To make Goosberry Wine

Ingredients: 12lb green gooseberries, gallon raw water & sugar.

Bitters

To make a pleasant Bitter

Ingredients: 1 quart brandy, the peel of a dozen oranges, 1 ounce gentian, a little saffron & cochineal.

Mead

to make mead. Sister Alsop

Ingredients: 1 gallon honey, 6 gallons cold water & a crust of brown bread.

A Summer Water

To make a Water to Drink in Sommer

Ingredients: strawberries, cinnamon, fair water & cloves.

Elderberry Ale & Rhubarb Ale

And finally here are the two most popular ales over on @shaxworld…

Enjoy!

By Sarah Powell

Sarah Powell is the EMMO Paleographer at the Folger Shakespeare Library: on Shakespeare’s World Talk as @S_Powell

Living in Shakespeare’s World

|

Ten Transcription Tips

Hello my fellow transcriber! If you are reading this hopefully you’ve already caught the transcription bug. If not, perhaps these ten tips will help persuade you to keep calm and carry on.

- Watch out for abbreviations. There are a few that occur regularly (with, which, etc). We’ve included shortcut buttons to make transcribing them easier for you.

- Watch out for spelling as it was not standardized. You’ll encounter all sorts of crazy and wonderful spellings. Perhaps you’ll even discover a new word for entry in the Oxford English Dictionary! [see Philip Durkin’s blog post on December 17th]. Sometimes it helps to say the word out loud as you see it… and remember we transcribe what we see. We don’t modernize spelling.

wendsday (wednesday)

wendsday (wednesday)  saterday (saturday)

saterday (saturday)

- Count your minims. Use the rest of the word to decide if it’s an ‘i’, ‘u’, ‘m’ or ‘n’.

minded

minded

- Don’t be put off if there’s something you can’t do. Remember the beauty of Shakespeare’s World is that you can leave out a word, a line, or even a whole chunk of writing if you simply don’t like the look of it! It might be right up the next transcriber’s street…

- Be prepared to encounter both majuscules (capital letters) and minuscules (lower case letters) where you wouldn’t expect them.

- Watch out for interference from letters above and below the line.

- Note the ‘y’ thorn, and the abbreviations it comes with: the, them, that…

the

the

- Use context to help you. If you work out 5 of 6 letters, you might be able to guess the rest. Once you’ve done so check your letter choice in the alphabet. Beware of getting too carried away with guesswork though; if you feel you are guessing a lot move on to a different image.

- Picking up on number 8: USE YOUR ALPHABET. Check your letters. It’s easy to use and it’s located in the side bar.

- Finally, and most importantly, enjoy it. Do as much or as little as you like. We are a transcribing community and we are all working together towards the same end. Thanks for contributing!

Sarah Powell is the EMMO Paleographer at the Folger Shakespeare Library: @S_Powell

Recent Comments