@shaxworld #paper #baking #thankyou

Our kitchens are filled with paper. We make our morning coffees by dripping water through a paper cone filled with freshly ground coffee grinds. We wrap our sandwiches for lunch in wax paper and line our cake tins with baking paper. Dry kitchen paper is often used to dry food before deep drying and damp kitchen paper is often used to preserve freshly cut herbs in the fridge. Many different kinds of paper thus aid us in performing a variety of quotidian tasks in our homes. Paper, in fact, might be the unsung hero in modern kitchens. Recently, as part of a new research project (more on that here), I began to wonder whether paper also performed similar roles in kitchens of the past.

Early modern recipe collections record detailed instructions to produce foodstuffs and medicines and are revealing of the way householders carried out a range of daily tasks in early modern homes. In fact, they are ideal sources to explore paper-use in pre-modern kitchens. However, the sheer number of recipes in the hundreds of surviving recipe books, each containing scores of individual recipes, makes the search for paper-use a little overwhelming and, at times, challenging for a single researcher. In short, I desperately needed the help of the Shaxworld community!

Luckily for me, over the last few months, the kind and wonderful members of Shaxworld have been tagging instances of paper-use in recipes with the label #paper. So far, around 20 recipes in 10 different recipe collections have been identified. [1] A glance through these reveals that, like today, paper served a multitude of uses in the home and was a used as a tool in both food and medicine production. Two common usages emerge from our sample: paper was used to line cake/biscuit tins and to apply ointments and salves. A few months ago, I took a look at paper used as plasters for The Recipes Project blog and so today I’d like to further explore uses of paper in early modern baking practices.

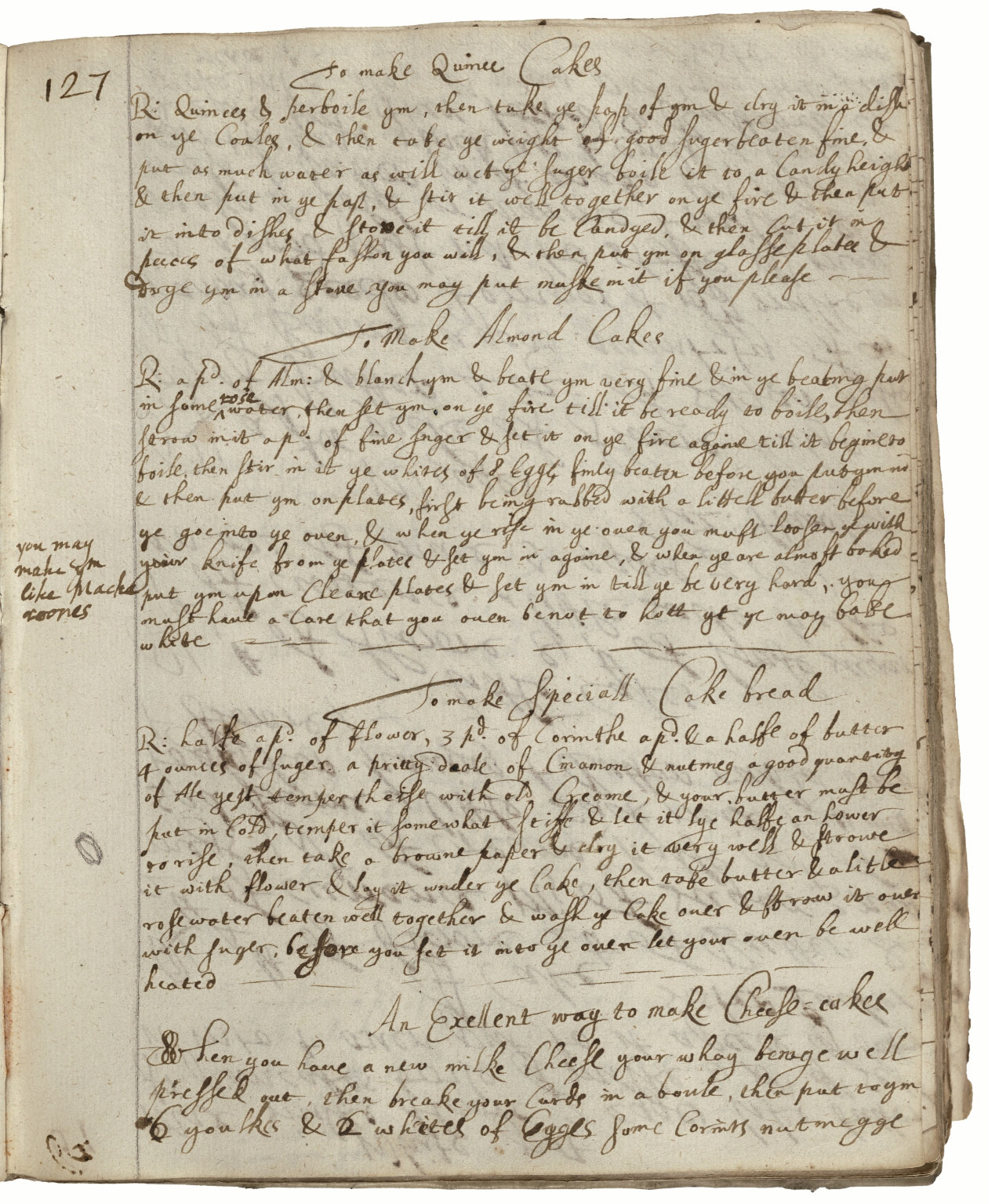

Page from the cookery book of L. Cromwell with the recipe to make ‘Speciall Cake bread’. Folger MS V.a.8, p. 127.

Within our sample, seven recipes use paper as a kind of liner. The recipe book for Margaret Baker, for example, has a recipe to make Jumballs (a kind of fine sweet cake or biscuit). The recipe advises users to warm and ‘creame’ together flour, sugar, egg whites and rosewater and ‘mould’ the resulting light paste in caraway or coriander seeds. These are then shaped into knots and baked on ‘flowered papers or tinn plates’ (Folger MS V.a.619, fol. 95r). Another recipe to make ‘Speciall Cake bread’ in the cookery book of a ‘L. Cromwell’ advises the baker to ‘take a browne paper & dry it very well & strowe it with flower & lay it under the cake’ (Folger MS V.a.8, p. 127). In the early modern period, the brown paper was often used as a wrapping paper of sorts by grocers etc. The request here to ensure that the paper is dry suggests that ordinarily the brown paper might be damp or wet in some way – perhaps this is a case where the brown paper was first rinsed and then reused? Aside from the cheaper brown paper, more expensive white paper was also used to line cake tins. Examples include the recipe ‘To make very fine cakes’ in an anonymous recipe collection (Folger MS V.a.19, p. 132) and a recipe to make marchpane (Folger MS V.a.364, the recipe book associated with Nicholas Webster, fol. 12v-13r) which both suggest the maker to bake on sheets of white paper.

In addition to lining cake tins and biscuit sheets, paper was also used to shape baked goods. A recipe for almond lozenges tells the maker to ‘fashon’ as they like upon plates or paper moulds (Folger MS v.a. 8, p. 133). Another recipe for cheesecakes recommends the baker to ‘pin papers about them to prevent their falls’ during the baking process (Folger MS V.a.8, p. 147).

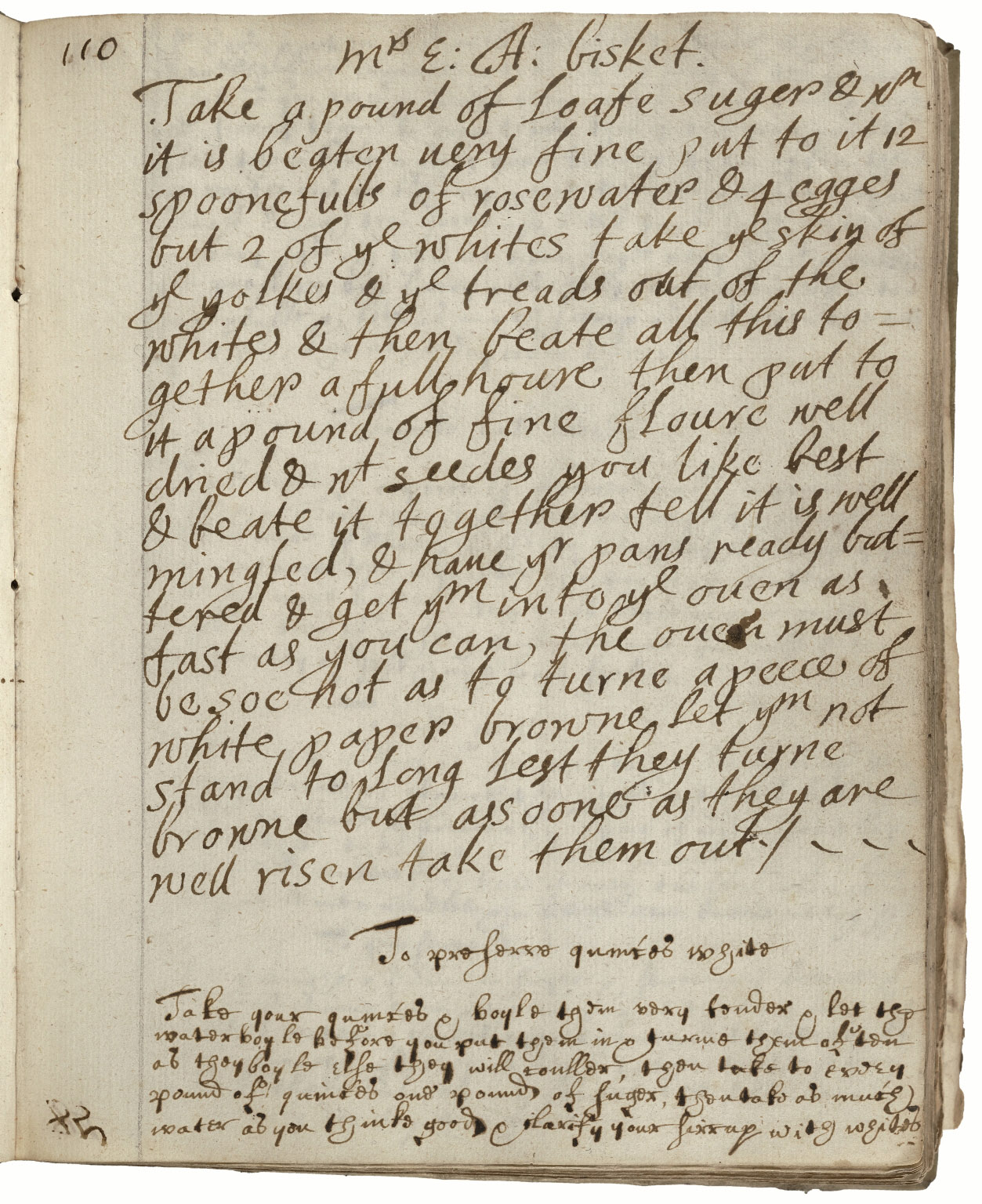

Recipe by ‘Mrs E’ for a biscuit. Folger MS V.a.8, p. 110.

Finally, paper, it seems, also helped bakers ascertain the heat levels of their ovens. One particularly interesting recipe for biscuits requires a particularly hot oven. The recipe instructs the baker to that the ‘oven must be soe hot as to turne a peece of white paper browne’ (Folger MS V.a.8, p. 110).

It seems that paper was a crucial tool for early modern bakers and was used in the production of a range of different baked goods. This discovery confirms recent suggestions that paper was not as scare, rare, and expensive in the early modern period as was previously thought. In fact, paper was used in a range of everyday tasks suggesting that it was readily available and probably fairly economical. Significantly, our recipe writers were, at times, quite specific about the kind of paper used. Our current sample is probably a little too small for us to tease out whether this was due to personal preference or whether particular baked goods (likely the more precious ones) required special lining papers. Moreover, the final example where white paper was as an indicator of heat demonstrates the ingenuity of householders in taking and re-purposing everyday objects.

The focus on paper-used in recipes has brought up a number of fascinating points and enabled us to delve deeply into everyday activities of early modern householders. I’m still at the beginning of my research and so if you spot paper in a recipe, please mark it with #paper and add it to our sample. I’m so grateful to everyone for your help with my project! A final word – every Tuesday in August, The Recipes Project blog will publishing posts on recipes and paper. So, if this topic tickles your fancy, do click, click, click over there and have a read.

[1] The collections are Folger Shakespeare Library MSS V.a.8, V.a.19, V.a.21, V.a.140, V.a.215, V.a.364, V.a.388, V.a.456, V.a.490, and V.a.619.

By Elaine Leong @elaineleong

Recent Comments