@shaxworld #paper #baking #thankyou

Our kitchens are filled with paper. We make our morning coffees by dripping water through a paper cone filled with freshly ground coffee grinds. We wrap our sandwiches for lunch in wax paper and line our cake tins with baking paper. Dry kitchen paper is often used to dry food before deep drying and damp kitchen paper is often used to preserve freshly cut herbs in the fridge. Many different kinds of paper thus aid us in performing a variety of quotidian tasks in our homes. Paper, in fact, might be the unsung hero in modern kitchens. Recently, as part of a new research project (more on that here), I began to wonder whether paper also performed similar roles in kitchens of the past.

Early modern recipe collections record detailed instructions to produce foodstuffs and medicines and are revealing of the way householders carried out a range of daily tasks in early modern homes. In fact, they are ideal sources to explore paper-use in pre-modern kitchens. However, the sheer number of recipes in the hundreds of surviving recipe books, each containing scores of individual recipes, makes the search for paper-use a little overwhelming and, at times, challenging for a single researcher. In short, I desperately needed the help of the Shaxworld community!

Luckily for me, over the last few months, the kind and wonderful members of Shaxworld have been tagging instances of paper-use in recipes with the label #paper. So far, around 20 recipes in 10 different recipe collections have been identified. [1] A glance through these reveals that, like today, paper served a multitude of uses in the home and was a used as a tool in both food and medicine production. Two common usages emerge from our sample: paper was used to line cake/biscuit tins and to apply ointments and salves. A few months ago, I took a look at paper used as plasters for The Recipes Project blog and so today I’d like to further explore uses of paper in early modern baking practices.

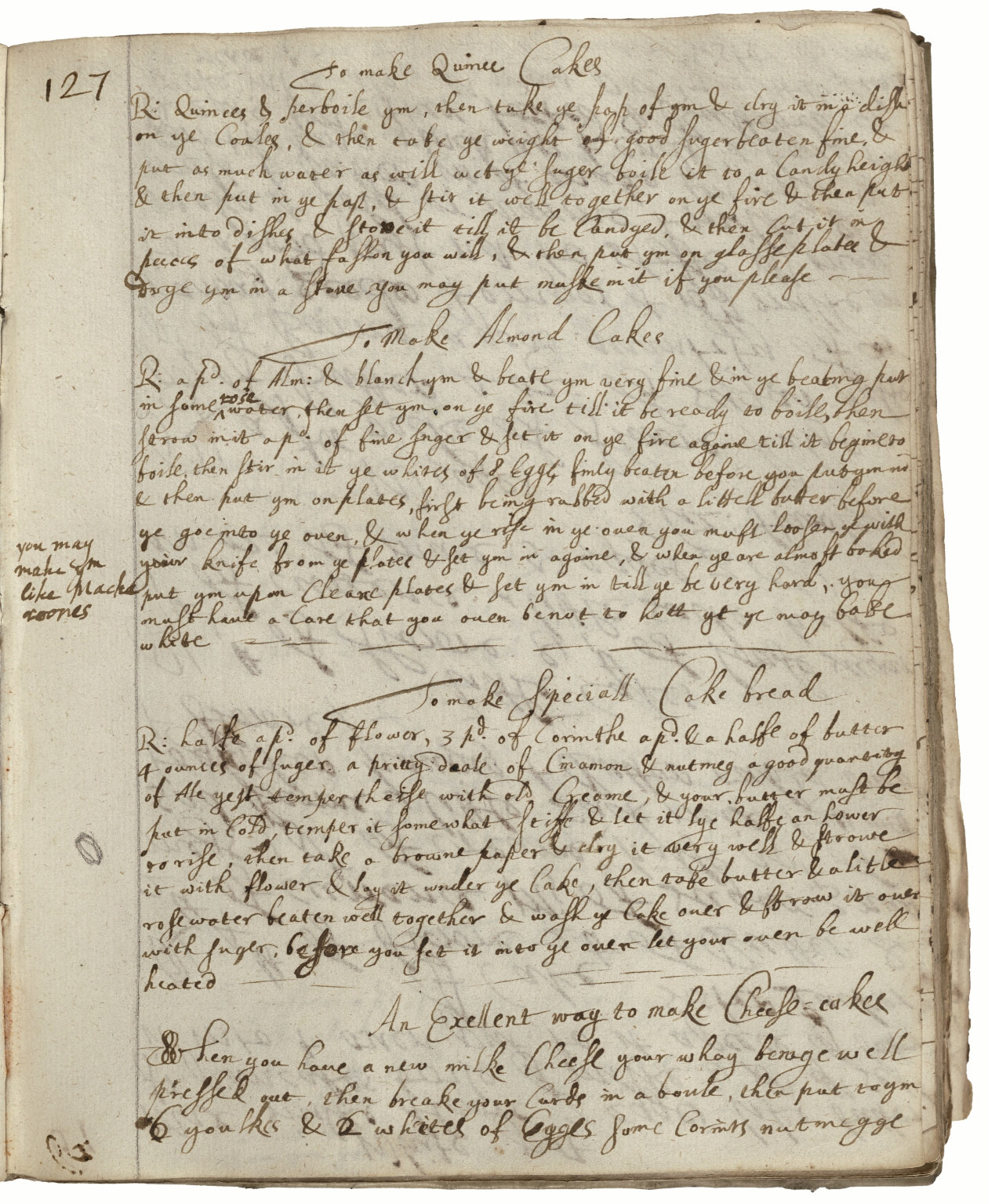

Page from the cookery book of L. Cromwell with the recipe to make ‘Speciall Cake bread’. Folger MS V.a.8, p. 127.

Within our sample, seven recipes use paper as a kind of liner. The recipe book for Margaret Baker, for example, has a recipe to make Jumballs (a kind of fine sweet cake or biscuit). The recipe advises users to warm and ‘creame’ together flour, sugar, egg whites and rosewater and ‘mould’ the resulting light paste in caraway or coriander seeds. These are then shaped into knots and baked on ‘flowered papers or tinn plates’ (Folger MS V.a.619, fol. 95r). Another recipe to make ‘Speciall Cake bread’ in the cookery book of a ‘L. Cromwell’ advises the baker to ‘take a browne paper & dry it very well & strowe it with flower & lay it under the cake’ (Folger MS V.a.8, p. 127). In the early modern period, the brown paper was often used as a wrapping paper of sorts by grocers etc. The request here to ensure that the paper is dry suggests that ordinarily the brown paper might be damp or wet in some way – perhaps this is a case where the brown paper was first rinsed and then reused? Aside from the cheaper brown paper, more expensive white paper was also used to line cake tins. Examples include the recipe ‘To make very fine cakes’ in an anonymous recipe collection (Folger MS V.a.19, p. 132) and a recipe to make marchpane (Folger MS V.a.364, the recipe book associated with Nicholas Webster, fol. 12v-13r) which both suggest the maker to bake on sheets of white paper.

In addition to lining cake tins and biscuit sheets, paper was also used to shape baked goods. A recipe for almond lozenges tells the maker to ‘fashon’ as they like upon plates or paper moulds (Folger MS v.a. 8, p. 133). Another recipe for cheesecakes recommends the baker to ‘pin papers about them to prevent their falls’ during the baking process (Folger MS V.a.8, p. 147).

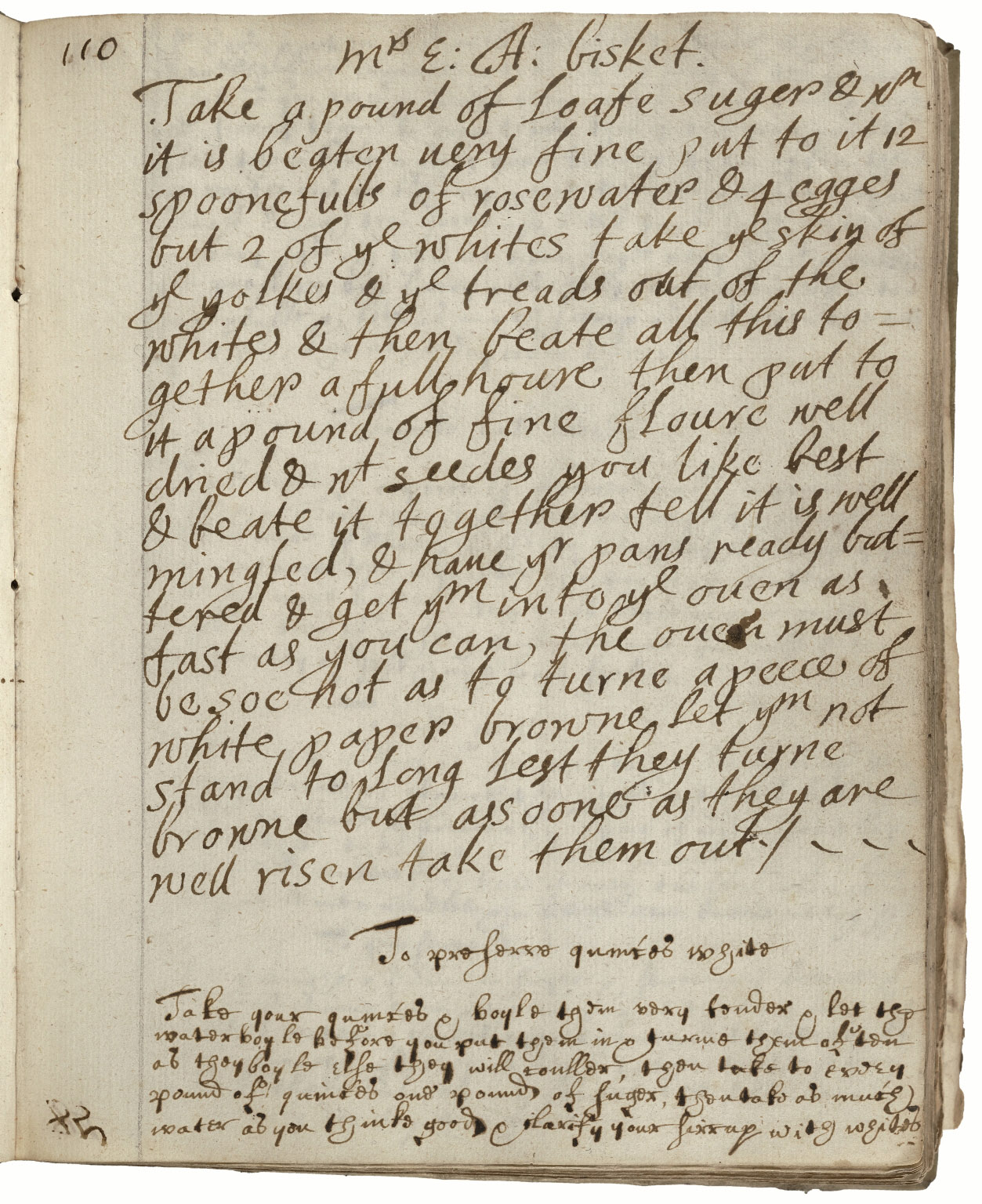

Recipe by ‘Mrs E’ for a biscuit. Folger MS V.a.8, p. 110.

Finally, paper, it seems, also helped bakers ascertain the heat levels of their ovens. One particularly interesting recipe for biscuits requires a particularly hot oven. The recipe instructs the baker to that the ‘oven must be soe hot as to turne a peece of white paper browne’ (Folger MS V.a.8, p. 110).

It seems that paper was a crucial tool for early modern bakers and was used in the production of a range of different baked goods. This discovery confirms recent suggestions that paper was not as scare, rare, and expensive in the early modern period as was previously thought. In fact, paper was used in a range of everyday tasks suggesting that it was readily available and probably fairly economical. Significantly, our recipe writers were, at times, quite specific about the kind of paper used. Our current sample is probably a little too small for us to tease out whether this was due to personal preference or whether particular baked goods (likely the more precious ones) required special lining papers. Moreover, the final example where white paper was as an indicator of heat demonstrates the ingenuity of householders in taking and re-purposing everyday objects.

The focus on paper-used in recipes has brought up a number of fascinating points and enabled us to delve deeply into everyday activities of early modern householders. I’m still at the beginning of my research and so if you spot paper in a recipe, please mark it with #paper and add it to our sample. I’m so grateful to everyone for your help with my project! A final word – every Tuesday in August, The Recipes Project blog will publishing posts on recipes and paper. So, if this topic tickles your fancy, do click, click, click over there and have a read.

[1] The collections are Folger Shakespeare Library MSS V.a.8, V.a.19, V.a.21, V.a.140, V.a.215, V.a.364, V.a.388, V.a.456, V.a.490, and V.a.619.

By Elaine Leong @elaineleong

The Mystery of the Elf Hoof

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

It’s not every day that you come across a recipe that calls for elf hoof. Not even when you regularly work with old manuscript recipe books. Nope. Not even when looking at an eighteenth-century grimoire, in which the most unusual ingredient is the white coating (thrush? milk?) scraped from a newborn’s tongue.

When I spotted @MyraMo and @mutabilitie discussing Margaret Baker’s remedy ‘For Convolchen fetts in yong Children’, I was initially drawn in by @MyraMo’s question about mouse heads and afterbirths. (Who wouldn’t be?) But the recipe became even more intriguing when @mutabilitie commented:

I reckon the ten-clawed hoof of a mountain elf mentioned at the beginning would have prevented anyone from actually trying out this recipe – probably just as well!

Afterbirth? Uncommon, but not unexpected. After all, I’d come across dried mummy, menstrual blood, spit, feces, and urine before. Mouse head? That, as it turns out, was merely a misreading of ‘dead man’s head’. While shocking to modern sensibilities, skull was an ingredient common enough to be listed in official pharmacopoeia. Elf hoof!? That was entirely unexpected—and certainly not a misreading:

Take the houf of an Elfe it is best that lives in the mountaine & hath tenn clawes upon one foote one of those clawes must be rasped and made into very fine pouder.

I didn’t initially dismiss the possibility of Margaret Baker truly meaning elf hoof. I’ve previously looked at the classification of hobgoblins and their ilk, but had not encountered any descriptions of the medicinal uses of supernatural creatures’ body parts. Elves, like any other supernatural being, could help or hinder humans. Given that early modern medicine regularly included human body parts, which were seen as particularly efficacious, surely supernatural body parts would be even better.

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

That said, ‘elf hoof’ was more likely to refer to some herb. The OED didn’t turn up anything obvious except for elf dock and elfwort, alternative names for elecampane. Culpeper’s The English Physician (1652) notes that this herb grows in shady places and, governed by the sun, is hot and dry in the third degree. It even looks like the sun and its root is like a hoof with claws. One species, orestion, grows specifically in the mountains, according to Robert Hooper (1817). As a stimulant and tonic, it is useful in treating old coughs, shortness of breath, windy stomachs, stopped menses and urine, gout, sciatica, and stitches in the side caused by the spleen. ‘Elf-shot’, a term dating back to the Anglo-Saxons, was still in early modern use to describe certain physical and mental disorders. For example, sharp and shooting pains, such as stitches, gout or sciatica, might be elf-shot.

Pretty convincing. The mandrake, however, is another contender. In The Compleat Herbal of Physical Plants (1707), John Pechey noted that it grows in woods and shady places and is a good narcotic. Culpeper, in the Pharmacopia Londinensis (1718), advised against the use of mandrake roots because of the dangers posed by it being cold in the fourth degree. It could, however, be useful for ‘such as have a frenzy’ (269). The mandrake, thought to be luminous, was governed by the moon and, as such, could be used to treat ailments such as epilepsy, an ailment associated with the full moon. Folklorists Thomas Dyer and Richard Folklard describe the mandrake’s various magical uses, ranging from love charms to treasure finders. Resembling the human form, mandrake roots were sometimes sold as little mannikins and (in early modern France) they were sometimes seen as a species of elf. Those who possessed mandrakes often cared rather elaborately for it, providing it with food and drink, much in the same way that one might try to keep other supernatural creatures within the household happy.

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

But which fits better with the remedy as a whole? In addition to elf hoof, skull and afterbirth, the ingredients were leaf gold, peony, cowslip, mithridate, nutmeg and amber. The remedy suggests that the convulsions were epileptic; it was to be administered at the change of the moon and several of the ingredients were intended to counteract the effects of the moon. For example, gold, amber and peony were all ruled by the sun. Other ingredients were intended as protective, such as the mithridate (a cure-all), the man’s skull (like cures like, in that epilepsy was also a disease of the head), and the afterbirth (acting symbolically). The ingredients in general had sedative and anti-spasmodic properties.

Receipt Book of Margaret Baker (ca. 1675), V.a.619, ff. 102r-102v.

Elecampane fits the description of elf hoof in that there is a specific type grows in the mountains, it treats ‘elf-shot’ (of which epilepsy might be one type), and it is associated with the sun like most of the other ingredients. Mandrake, in contrast, stands out as being a cold ingredient. It fits in other ways, however: it had narcotic properties and was associated both with diseases of the moon and elves.

The recipe blurs the magical and medical in intriguing ways with several of its ingredients and timing of administration. It also suggests the complicated pathways of transmission over time. Elf hoof may very well have been a local term, or one that simply made it into Margaret Baker’s collection when she heard it from someone else and it took her fancy. The remedy also hints at the continued existence of much older ideas: sun and moon, elf-shot, and mannikins. In the end, for the modern reader, Margaret Baker’s description is both incredibly specific and frustratingly vague. The elf hoof that she describes in great detail no longer corresponds to our modern terms, leaving a recipe that seems more mysterious than it probably was at the time.

What do you think it was: elecampane, mandrake… or elf?

And …why we love recipes

In the inaugural post of the series, Heather Wolfe made a passionate case for why we need to transcribe and study the tens of thousands of early modern letters in our libraries and archives. Today, we turn to the wonderfully rich world of early modern recipes. Recipe books, like letters, are common finds in archives and the Folger Shakespeare Library has an exceptional collection of these fascinating texts.

In this recipe booking compiled by Margaret Baker in the 1670s, we can see how she wrote down a medicine against the plague on one page and recipes for almond cakes on the other.

In Shakespeare’s England, many households had a notebook in which they jotted down culinary, medical and household recipes. These short texts gave readers instructions to make a wide range of products from roasted pike to cough medicines and sustaining broths to ways of keeping linen white. The miscellaneous nature of these texts reflects the multifaceted role taken on by householders and household managers in the period. The close juxtaposition of culinary and medical recipes, reminds us of the close association between food and medicine; for example, you might see a remedy for a fever listed next to a recipe for a pie. This is due not only to the holistic nature of humoural medicine, but also to the crossovers between the spaces, technologies and materials used to produce food and medicines.

Useful for the holiday season – recipes to bake a rump of beef and to make sausages.

Recipes to make a range of foodstuffs—cheesecakes, pies, stews—give us an idea of the kinds of foods served on early modern tables. By transcribing a large number of recipes, we can track food fads and fashions, continuity and changes in the country’s food staples and much much more. After all, with Christmas coming up, you might be interested in learn that turkey (roasted, in pies or as turkey hash) also graced tables around this time in seventeenth-century England. Recipe books also open a window into other “housewifely” tasks such as the making of different kinds of cheese and the brewing of beer and ale. As many of the recipe books that we’re transcribing in Shakespeare’s World were created by well-off gentlewomen, one might imagine that these tasks were done by teams of housekeepers, dairy maids and cooks rather than a lone housewife in the kitchen.

Fearing a fever? This is the recipe for you!

As you work through our recipe selections, you’ll encounter scores of health-orientated recipes. Cough syrups, medicines for the jaundice or remedies for the ague are dotted throughout the recipe archive. These recipes reveal the everyday anxieties and health-concerns of men and women living in early modern England and the many ways in which they tried to ease their symptoms. While there were various options for medical care in the period, family and friends often served as the “first resort” for patients seeking to alleviate their ailments or sicknesses. Then, as now, men and women tended to mix commercially available medicines with those made in the home. After all, whom among us has not mixed an over-the-counter pain-killer with a home-brewed honey, lemon and ginger “tea” during bouts of cold and flu?

You might wonder from where householders gathered all this medical and culinary information. The answer here is, as always, a complex one. Much like how we might build up our own “family cookbook”, householders in the early modern period relied on their networks of family, friends and neighbours, contemporary printed books and encounters with experts—medical practitioners, farriers, tavern maids—to fill their recipe books. After all, who would better know how to keep bottles sweet smelling than someone who works in the pub?

Interested and would like to learn more?

- Here is my feature story on recipes in early modern households.

- The Recipes Project is a collaborative research network exploring histories of pre-modern recipes.

- EMROC is a research-led teaching experiment where students work to create transcriptions and a database of early modern English recipe books.

- For more on food in the period, see, for example, Joan Thirsk’s Food in Early Modern England (London, 2007).

- A wonderful introductory text to medicine in early modern England is Andrew Wear’s Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680 (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

All examples in this post are taken from the recipe book of Margaret Baker which was compiled around 1675 (Folger MS v.a. 619, fols. 81v-82r, 79r and 54v.) The manuscript is available in entirety here and is included in Shakespeare’s World.

By Elaine Leong @elaineleong

Recent Comments