No Foot, No Horse

He’s mad that trusts in the tameness of a wolf, a horse’s health, a boy’s love, or a whore’s oath.—Fool, King Lear (3.6.18)

Receipt books in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s collection contain not only remedies for human ailments but also cures for domestic animals such as horses. Such a receipt book, MS V.a.140, contains three pages of remedies (fols. 6v/7r, fols. 7v/8r, and fols. 8v/9r) for common ailments of horses. Of the seven ailments mentioned in this manuscript, four involve the horse’s feet or hooves.

There is an old saying among horsemen, “No foot, no horse.” Despite their size and strength, horses are notoriously fragile animals. Four slender legs and small hooves must bear the horse’s full weight of eight hundred to two thousand pounds. Horses were essential to the economy and society of Shakespeare’s time. British economic historian Peter Edwards, author of Horse and Man in Early Modern England (2007), has written extensively on the importance of horses in early modern England. Not only were they a source of transportation, horses were also essential to mounted warfare, agriculture, and courtly pastimes such as tournaments, hunting, and manège riding (dressage). Therefore, horse owners paid particular attention to the care of their horses’ feet and hooves.

Veterinary medical training in Britain was not formalized until the founding of the Royal Veterinary College in London in 1791. Louise Curth, a historian of veterinary medicine at the University of Winchester (UK), writes about the range of practitioners who treated equine illnesses in “A plaine and easie waie to remedie a horse” : equine medicine in early modern England (2013).

Curth explains that many recipes for treating illness in horses were transmitted orally among horse healers, yet some of these remedies were written down and circulated in manuscript form. Horse remedies even appear in family household and receipt books such as Folger MS V.a.140. In the early modern period, a whole genre of hippiatric texts on the care and treatment of horses appeared in print throughout Europe and England. Gervase Markham (c. 1568-1637) authored several manuals on horse training and care which enjoyed wide circulation in the seventeenth century. Markham’s Maister-peece (1638) in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s collection is but one of several hundred early modern hippiatric texts in print.

The freelance horse doctors or “horseleeches” were at one end of the spectrum. (“Leech” does not refer to the practice of letting blood, but instead is a corruption of the Old English word for healer, læce). Farriers or marshals (derived from the Anglo-Saxon word for “farrier”) not only fit shoes to horses’ hooves, but also treated equine illnesses. The most prestigious farriers—those hired by the noble classes to cure their valuable steeds—belonged to the London Company of Farriers (est. 1356).

Title page of Markham’s Maister-peece (1636) showing horseleeches treating horses for various ailments. Folger Shakespeare Library STC 17379.

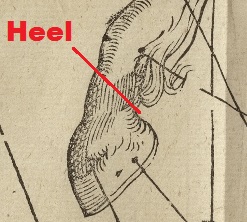

The Folger’s receipt book V.a.140 contains four different recipes appear for treating “scraches in a horse heels” on fol. 8r. The “heel” refers to the rear part of the horse’s pastern. (The “pastern” extends from the coronet band of the horse’s hoof upwards to the fetlock joint).

Detail of heel area from horse diagram (shown above) in Gervase Markham, Markham’s Maister-peece (1636), STC 17379, Folger Shakespeare Library.

Since the heel is close to the ground, it susceptible to dryness, cracking, and sores caused by injury and exacerbated by caked mud and soil. Here is a transcription of the recipes:

for the scraches in a horse heels

Take tarre hogges grease iij or iiij cornes of

baye salts & boyle it togeather then take an

olde cloth & dyppe it therin & anoynte the

sore there with as hotte as the horse maye

abyde it for scaldinge and then sewe or

bynde the same cloth close about it & it will

cure it */ or thuse

Take blacke sope & mustard& mingle them

well toogeather and anoynte the sore ther

with every daye till it be hole remembringe

to kepe your horse heles from wett vntill

they be hole/ * or thus

Take tarre hogges grease a litle deare

suett mayes butter and culvers donge

and boyle it togeather & make a plaister

therof and seed and sooe it close & as hott as the

horse may abyde it over all the sore &

dresse it every three dayes and kepe his

hele drye and it will heale it~

*or thus

Take halfe a pounde of freshe grease & a qua

=rteren of a pounde of brymstone & a nounce of quicke

sylver & mingle then togeather & anoynte the sore

therwith & it will heale it.~

“For the scraches in a horses heeles,” Receipt book [manuscript]. c. 1600, fol. 8r, MS V.a.140, Folger Shakespeare Library.

“Brymstone” is the element sulphur and “quicke sylver”—liquid mercury. Sulphur and its compounds act as an antibiotic and fungicide in medicines used to treat dermatological conditions.

“Culvers donge” is the droppings of a dove or pigeon. Animal droppings (particularly bird and cattle dung) appear frequently as ingredients in hippiatric cures. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, mustard was once used as an ingredient in poultices and plasters. Curth cites an early modern receipt book (MS 144) in the Wellcome Library which contains a recipe on fol. 320 for treating “Scaby heeles.”

Recipe “for a horse that have Scaby heeles.” A book of receiptes, c. 1650-1739, MS 144, Wellcome Library, London.

The recipe in the Wellcome MS 144 uses two of the same ingredients—black soap and mustard—as that in the Folger MS V.a.140, and substitutes “hennes dunge” for culvers dung. Authors of printed hippiatric manuals also prescribed similar ingredients for treating sores of the foot. Gervase Markham, in chapter 105 of his Maister-peece, describes a remedy for the “Crown Scab,” a type of sore “breeding round about the Corners of the Hoof” (p. 227). Markham provides two remedies, the second on p. 228 which combines “Soap,” “Hogs-Grease,” “Bole-Armoniack” (Armenian bole, a red earth used in gilding), and “Turpentine” (resin from pine or other coniferous trees) in a plaster.

Since the same ingredients appear in early modern manuscript and printed sources for treating similar equine foot ailments, one may deduce that these remedies may have actually been effective and thus made their way into the vernacular knowledge of horse healers. Several commercially-manufactured ointments for horses’ hooves and heels (such as Absorbine Hooflex) on the market today contain such ingredients as cod liver oil, neatsfoot oil (derived from cows’ feet and shin bones), zinc oxide, tallow (animal fat), and pine tar.

Times have changed, and humans no longer rely on horses in daily activities, although horses still play an important role in sport and recreation worldwide. Yet some equine healing practices, both the treatment and the ingredients, have remained quite similar to methods used four centuries ago.

Recent Comments